Zombie Biology, Social Technology, and the Hivemind

Meet Poppy - the apocalypse will be live streamed - fungus garden - hivemind

Zombie biology

Zombies have been around for a while. In an ancient Sumerian text, Ishtar's Descent into the Underworld, the goddess Ishtar threatens that she shall,

… raise up the dead and they shall eat the living:

And the dead shall outnumber the living!

The word ‘zombie’, however, found its way to the world via Haitian folklore, where Vodou rituals could turn people into living dead. Intrigued by these living dead, Canadian anthropologist E. Wade Davis traveled to Haiti in the early 1980s. The result is an ethnobiology of the Haitian zombie. He learned that two concoctions can induce a zombie-like state, one based on pufferfish toxins, the other based on datura flower poison.

Welcome to zombie biology1.

Let’s start with a well-known example. This is a Camponotus leonardi ant, or Poppy for her friends. Poppy is not a happy ant.

Poppy is not a happy ant because she’s dead and has been zombified by a fungus called Ophiocordyceps unilateralis2. Poppy and her friends live in the canopy of tropical forests in Southeast Asia. Occasionally, they cross gaps in the canopy by trundling across the forest floor. There, they are exposed to fungal spores.

Once Poppy is infected, she has four to ten days to live. But, like a good zombie, she begins to change sooner. With odd, jerky steps, she descends from the trees again. She shuffles to a leaf that hangs about 25cm above the ground, where the conditions for the growth of fungal spores are perfect. Once she finds a sturdy vein on the leaf she bites down with a famous ‘death grip’. Locked in place, the fungus bursts from her dorsal pronotum (the back of the neck, so to speak).

How does the fungus do this? How can fungal cells ‘take over’ an ant so completely?

As biologist Theodosius Dobzhanksy wrote in 1973: nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution. And we have a 48 million-year-old fossil of a fungus-infected ant chomping down on a leaf. So, Poppy’s story involves a long evolutionary arm’s race of trick and counter-trick that has given the fungus an impressive arsenal of behavior-changing molecules to deploy3.

First, the fungal spores secrete enzymes (chitinase and protease) to dissolve little patches of the ant’s armor. Once inside the ant, fungal cells enter the brain, where molecules like sphingosine and guanidinobutyric acid change the ant’s movement behaviors. Then, when the infected ant finds herself in a spot with a good temperature and humidity, the fungus messes around with the muscles that control the mandibles (possibly atrophy by reducing leucine and mitochondria). Result: ant jaws clamp shut.

That is a scary example of behavioral control by a parasitic fungus. But humans are not ants, so we’re fine. Oh, wait.

Zombie apocalypse, the live stream

Toxoplasma gondii is a single-celled parasite that is responsible for toxoplasmosis. Normally, T. gondii infects rodents and their predators. But it can also infect humans.

Infected rodents’ behavior changes to increase their chance of getting eaten. They become less risk-averse and more exploratory. Humans are not exempt from this behavioral modification. Infected men are more suspicious, jealous, and risk-taking; women show the opposite trend. Infection with T. gondii also affects motor performance, which may partially account for the higher risk of traffic accidents. People (especially women) carrying the parasite are also more likely to show more tribal beliefs and are at higher risk for schizophrenia. No surprise that infected people are also more likely to major in business and engage in entrepreneurship…

But correlation is not causation and averages tell us little about individuals.

Fortunately, we don’t need biological parasites; we can now rely on technology to turn us into zombies. That’s the argument author Rebecca Solnit makes in this great op-ed (which I encourage you to read entirely4).

Nobody’s home. Not in the young woman with the big headphones cycling against the light. Not in the person in the middle of the crossing staring at their phone, or the person talking to someone who’s not there and ignoring the one they’re pushing in the baby carriage, or the distracted driver who doesn’t seem to notice those cyclists and pedestrians. So I move through a world of people who are not all the way there and sometimes hardly there at all – and who don’t seem to want anyone else to be there either.

…

Some of the justification for the withdrawal seems to be efficiency – the capitalist sense that time is money and you need to hoard the former so you can work incessantly to earn the latter. Another piece of it is the idea that the activities of daily life are so tedious and burdensome that you should try to avoid them.

Modern zombies are the living dead, shuffling with jittery steps5, hungry for human brains. This cultural image was born with George Romero’s 1968 movie Night of the Living Dead. Earlier zombies, like the Haitian ones, were raised from the dead by someone. What makes zombies so scary is the sense that they have no control and, in their earlier Haitian incarnations, are controlled by others.

This lack of control, the mere survival through simple reflexes, could make the rise and fall of zombie popularity a ‘barometer of cultural anxiety’. The economy shivers, the climate crumbles, and wannabe dictators throw thousands of innocents into horrible wars. We feel out of control and so we are drawn to movies and stories about heroes who stand up against a mindless tide of zombies that mirrors our fears of losing control. And let’s not forget the companies that crave our undead datafied souls. Solnit makes a similar point,

If you object that we’re not in a zombie movie because there are no brain-eating cannibals, let me reassure you, there are. The corporations are devouring our attention, and chewing our lives down to the bone to get at our data. They have shown their ruthlessness in what they offer as long as they capture us and extract our attention, information and other assets from us.

But surely we are not yet lost? If our zombification results from a parasite or virus (real or virtual), can’t we use our metaphorical immune system? If it is the result of companies sucking our sweet virtual souls dry, can’t we change our interaction and consumption patterns? Solnit is not optimistic, even if she retains a glimmer of hope.

I hear stories of young people consciously rejecting smart phones and online life, and finding ways to connect in person – but they’re salmon swimming upstream. Their resistance is valiant, but individual will is far from adequate to escape the grasp of these corporations and recommit to the fading world of the here and now and embodied and gregarious. I don’t have a sweeping solution, but I think recognising that one of our deepest human desires is to connect, to belong, to be at home, and that doing so is made up of innumerable small in-person acts, might be a start.

Why don’t we skip hope and optimism and venture straight into the weird fungal gardens of Eden?

Fungal gardens and mutualism

Let’s remember poor Poppy the ant and the fungus that killed her.

However, the relationship between ants and fungi doesn’t have to be parasitic. Quite the opposite. The oldest farmers in existence are likely ants that tend to fungal gardens. By using plant matter as ‘soil’ for edible fungi, ants of the Attini tribe secure a source of supplemental arginine for their diets. The fungus gets shelter and food and in return, it provides protein in the hyphae, as well as carbohydrates and lipids in the staphylae — a bouquet of swollen tips at the end of hyphal strands that (at least) one line of fungi grows to specifically feed its tending ants.

The problem is not fungus; the problem is the shape of the relationship between ants and fungus. What if the same is true for human zombification?

It’s not the technology; it’s how we use (and are being used by) it.

Looking at the rise of the smartphone/social media, it’s easy to see a correlation with a dwindling number of friends, higher levels of reported loneliness and mental health issues, and so on.

But what if the phones and social media platforms are a symptom of something else?

More precisely, and Solnit hints at this in the second quote above, we see smartphones, social media, and their cousins as zombie-makers because they illustrate the extractive nature of supposedly social technologies. They toggle our cognitive mechanisms - the ‘zombie within’ - to capture our attention so that they can extract data and replace thoughts with advertisements. Technology, of course, never evolves in isolation. So let’s add an increasingly individualistic society (again already mentioned by Solnit) obsessed with pointless growth, efficiency at the cost of nuance, and meaningless metrics. Welcome to the age of the solopreneur.

There is nothing intrinsically wrong with growth, efficiency, or metrics, but the pursuit of them as it is now is illusory and inflationary. It’s parasitic, like the fungus that killed Poppy. So why not turn our relationship with technology, and social media specifically, into a mutualism, like the gardening ants?

My critical notes on social media/smartphones come from my conviction that these could be great technologies. For example, using a smartphone for communicative purposes increases well-being and, during the pandemic lockdown, it increased friendship satisfaction and reduced anxiety. Not all studies agree, but this suggests that there are at least some situations and uses in which smartphones can enrich our lives. Likewise, we hear all about the negative effects of social media, but it can have positive effects too, for example, by increasing psychological well-being through social bonding. Many people, especially from minority groups, who struggle to find a community in real life can find one online.

The platforms that could have a truly social purpose currently rest on foundations of engagement-driven algorithms. The goal is not to have you connect to others in meaningful ways but to get nudged into clicking and liking6 and spending as much time as possible on the platform. Of course, there are great places and groups on social media, and I’ve met people I would not have met otherwise. Yet, that requires a conscious effort on the part of the people involved. By relying only on the shallow illusion of (often anger-driven) engagement, potentially connective platforms are now ratcheted into attention-grabbing zombification tools. It need not be that way. We can still choose who we interact with and in what way.

Do we resign to zombie-like brainrot or do we grow a garden?

For now, we still have that choice.

Epilogue: Hivemind

At this point, our lovely ant Poppy is nothing but an empty husk.

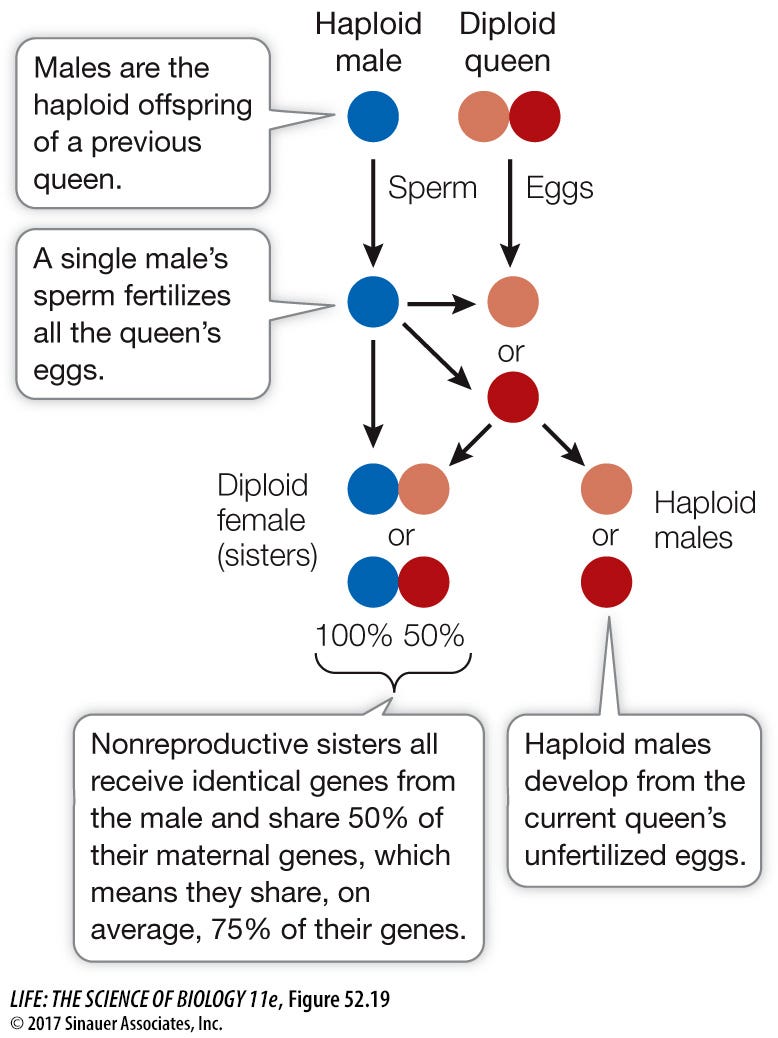

Part of her, though, lives on. High above her desiccated corpse, in the canopy, hundreds of her sisters keep the colony alive. Due to the sex-determining system of many eusocial species - haplodiploidy7 - Poppy shares (on average) 75% of her genetic material with her sisters. These colonies of close kin are called ‘eusocial’ because they have a division of labor with reproductive and non-reproductive castes, overlapping generations, and cooperative brood care.

In a way, we can see these colonies as organisms. Soldiers are the immune systems, workers the metabolism and maintenance, queens and male drones the eggs and sperm… Ant colonies, beehives, and termite mounds are all considered ‘superorganisms’. What about human societies? Already in 1895, biologist, sociologist, and anthropologist Herbert Spencer argued that ‘a society is an organism’. If humans are all part of a superorganism, it is a flimsy one. We’re not as tight-knit as a eusocial colony (although some scientists argue that we have some eusocial-looking traits, including, maybe, our shrinking brains).

But evolution rarely stands still.

Please put on your science fiction safety belt.

The year is 2047.

After the collapse of Neuralink in an avalanche of scandals, one of its competitors, Oriother, successfully launches the FeelYou. The neural biohybrid lattice allows you to share your feelings with others directly from brain to brain. Of course, it takes practice. No two brains are alike. But, the brains of teens and young adults especially are malleable enough to reshape themselves in response to new stimuli. FeelYou goes viral on augmented reality feeds all over the world.

The year is 2049.

Jeanie looks at the syringe Elly is holding and at the silver drop in its barrel. She squints when she tries to see the microneedle as thin as a hair. “That’s it, huh? The mercury that’ll coat my brain?”

“It’s way cooler than that,” Elly says. She seems present even if, lately, Jeanie noticed her zoning out more and more. “It’s modeled after fungal networks.”

“Fungus for my brain. Cool.” They’ve had this conversation before and Jeanie is already convinced. She’s using humor to hide the twinge of anxiety that twists her stomach like a wet rag.

“Think of it as a symbiont. You already have fungi in your gut microbiome anyway.” Elly smiles at her. Jeannie has the awkward sense that Elly is not the only one smiling and squirms in the synth-leather chair. “Biology is made for contingencies,” Elly adds, “machines are made for standardization.“

“Are you sure it’s not going to hurt?”

With an index finger, Elly taps her temple. “There are several surgeons in here.”

“Yeah, not creepy at all.”

Elly moves behind her. “Just lean back. You won’t feel a thing.”

A needle in your brainstem doesn’t sound painless, but Elly doesn’t lie. Right? Through the hole in the chair’s headrest, Jeanie feels Elly brush aside her hair. Then there is a dab of cold disinfectant at the top of Jeanie’s neck.

“There. Done.”

Jeanie sits up and gingerly touches the back of her neck. “That’s it?”

“Yep. It’ll tingle for a few days and then the inside of your skull will start to itch. That’s when the hyphae thread themselves around your neurons and microglia.”

“Not creepy at all. Or did I say that already?” Jeanie gets up from the chair. She stumbles, light-headed.

Elly is right there and steadies Jeanie with a hand on her elbow. “Take it slow.”

The year is still 2049.

It’s been three days. The inside of Jeanie’s skull is itching. Elly sits on the sofa next to her. “Totally normal,” she says. “It always begins with dreams. Those are the impressions of the others who share your FeelYou strain.”

“It’s… different than I expected,” Jeanie says.

Elly puts a hand on Jeanie’s thigh and for a second Jeanie feels herself putting a hand on… herself. “"I know. It’s not one-to-one. Your brain is still making sense of it. Like seeing a movie through frosted glass, right?”

“Yes, Exactly.” Did Elly read her mind? Can she do that now?

“And the headaches?”

A squeeze of a hand (her hand? No, Elly’s hand) on Jeanie’s thigh. “Differ from person to person.”

Jeanie grunts. “I’m one of the lucky ones, huh?” She leans back in the sofa and closes her eyes. She feels so much and she doesn’t know if the feelings are all hers. And the headaches. And the itching. The incessant murmur. All of it is so much, it’s too much, it’s —

Something clicks and the universe becomes a warm embrace.

The year is 2051.

Jeanie stares at her hands and wonders if they are still hers. The fingernails, the knuckles feel foreign. She tries to count the lines on the middle knuckle of her index finger but loses count each time. She is her, but she is also more. Is she happy? Parts of her, of her extended her, are.

Her hand is tan and strong, black and fine, pale and dappled with freckles. It’s not hers; it’s theirs. Her thoughts flow through the hive, reverberating understanding. She’s not alone. They are never alone.

FeelYou defied even the most optimistic expectations. Its biological components evolved quickly. Integration proceeded with leaps and bounds. Now, they are Jeanie and they are more. Decisions are made through consensus; hierarchies have crumbled; knowledge and resources are, for the first time, truly distributed.

There are other hives, of course. But in time, they will converge. Or self-destruct.

Science fiction, of course.

And yet.

We can already enable brain-to-brain communication in rats where one rat learns a sensorimotor task and the other rat learns that information through nothing more than the brain-to-brain interface. Granted, rats aren’t human. But what about BrainNet, where three humans played Tetris together with a “multi-person non-invasive direct brain-to-brain interface for collaborative problem-solving”? The technologies are crude at this moment, but the role of emerging technologies in building collective minds might soon become relevant.

You feel me?

Thanks for joining the hiv— I mean Subtle Sparks. If you appreciate the work behind these posts and want to keep them coming, consider sharing them, clicking like buttons, and all that algorithmic jazz.

If you’re looking for zombie philosophy, check out Consciousness, Zombies, and Brain Damage (Oh my!) by

and The P-Zombie Argument by . Or, if you want to know more about common human fungal infections, check out Some like it moist by . If you can’t get enough of fungi (and why would you; they’re awesome), I highly recommend Merlin Sheldrake’s Entangled Life — one of the best biology books I’ve read in a long time.This fungus inspired the video game and popular TV adaptation The Last of Us.

We still don’t have the complete story of fungal mind control, which is especially concerning knowing that antifungal-resistant fungal infections are a rising but understudied global threat to human health. A recent study that looked at the rapid rise of resistant fungi that can infect humans has a fun conclusion,

The diversity of the fungi themselves and the drivers of their emergence make it clear that we cannot predict what might emerge next.

Not only because it’s a great complementary piece for my recent Phoenix Avatar post. Hint hint.

Except when they’re dancing in Michael Jackson’s Thriller or attacking in World War Z. The ‘fast zombie’ trope was probably born in 1990s Japanese video games.

And yes, ironically, I want you to click and like my posts — such is the algorithm I have to contend with.

Cool article. I like the parallels you've drawn between Cordyceps and social media, and I love your inclusion of the Attini farmer ants.

If you did not already know this, you might be interested to know that why humans (and other vertebrates) do not have something like parasitic zombie fungus cordyceps when so many invertebrates do is because we have adaptive immune systems. Our immune systems with our B- and T-cells can develop a "learned," "memory" immune response to things like fungi, but invertebrates largely cannot. Fungi are, in general, terrible at surviving against a vertebrate immune response, which is why dangerous fungal infections in people are so rare (*unless they're badly immunocompromised) even though fungi arguably make up the majority of living mass on planet Earth.

The brain parasite that can live in humans that you cite, Toxoplasma, is better able to survive against vertebrate immune responses because it's already adapted to live in other vertebrates--but it doesn't largely make them sick (*unless they're very immunocompromised.) The effect sizes for the behavioral changes you mention in people infected with Toxoplasma are tiny, so it's controversial whether Toxoplasma actually enhances risk tolerance or aggression in people. This is again because of our awesome adaptive immune responses.

Individual ants, as invertebrates, don't have an adaptive immune response, but perhaps a colony of ants, as a superorganism, does. Individual ants don't seem to have much capacity to learn or make decisions, but the superorganism that is the colony may.

Humans have the advantage of being able to respond to a parasite on both an individual and a social level. I think this is both true on the level of an individual adaptive immune system vs. a fungus, and on the level of an individual mind vs. a digital parasite.

"extract data and replace thoughts with advertisements"

Sometimes just a few good words stand out proud and shiny. Well done Gunnar! 👏

I think The Matrix movies are still the best representation of the human/tech dilemma we face. Which of us is wise and strong enough to give up the (symbolic) juicy steak and woman in the red dress (or whatever our object of desire might be) in favor of mundane "reality"?