Phoenix Avatars and Main Character Syndrome

An extinct mystery bird - you, avatar - me, main character

To rise again, phoenix

The problem with rebirth is that you have to die first.

Even the mythical phoenix, the exemplar of rebirth, has to reduce itself to ashes before it can be reborn.

But the allure of rebirth is strong enough to want to burn ourselves. After all, many cultures have phoenix-like birds in their mythologies. The word itself likely comes from the Greek φοῖνιξ (phoinix), which has an uncertain meaning. It could mean griffin - that other mythical creature - or palm tree. However, a better clue is that phoinix also provides the root for ‘Phoenician’ to refer to the ancient civilization of traders in the eastern Mediterranean.

Perhaps that is where we need to look for the rebirth bird.

Descriptions from Roman sources like Pliny the Elder and Herodotus suggest that the mythical phoenix was based on the Golden pheasant (Chrysolophus pictus), a colorful bird originally from the Far East. Others, like the early Christian writer Lactantius, describe a larger bird, possibly the Goliath heron (Ardea goliath), a red-headed heron from sub-Saharan Africa. The Goliath heron is the world’s largest living heron, with some individuals standing at 5’ (~152cm).

But, there is a mysterious third contender as inspiration for the phoenix. In the 1970s, a mysterious bone was found during excavations on the small Umm-an Nar island in the Persian Gulf (closer to the Phoenician home base than the other two birds). It was a partial leg bone of a heron, significantly larger than the same bone in the Goliath heron, putting the mystery heron between 6’ and 6’6” (~183cm to ~198cm)1. A few bone fragments from the same site appear to belong to the same species, but beyond the description of these bones in a 1979 paper, we know little of the bird that has become known as the Bennu heron, named after the Egyptian deity, Bennu, a human-sized heron that represents… rebirth.

Mystery history lesson over.

Let’s jump to the present and future.

Technology, after all, has ensured that we don’t have to put ourselves on fire to reinvent ourselves. All we have to do is create an account.

Choose your avatar

In many role-playing games (RPGs), you can ‘assemble’ your player’s avatar. Are you human or another creature? Male or female or non-binary? Do you have special powers or skills? Cloak or armor? Magic or muscle?

People don’t choose or assemble their game avatars randomly2. Most avatar choices are driven by either actualization (representing how you see yourself) or idealization (representing what you wish you were), with option two having a higher risk for game addiction. The avatar choice is not inconsequential either. A meta-analysis found a small but consistent ‘proteus effect’ — people subconsciously begin to behave more like their avatar. The opposite is true as well. Your avatar can give away clues to your personality. For example, even simple digital game avatars can help people assess your extraversion and agreeableness.

Of course, this is only about games.

But we do the same on social media (and beyond)3.

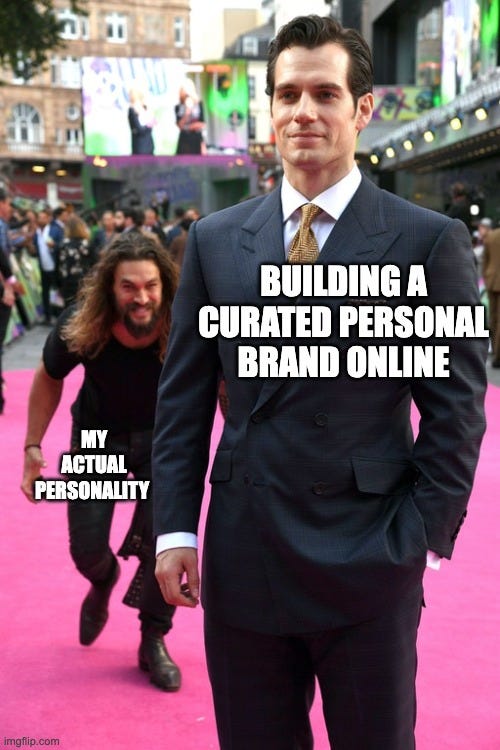

Which profile picture do I choose? Do I use my real name? What do I put in those few words of my bio? Which identity labels do I claim? And that’s only the start of it. Do I share everything that pops into my head? Do I want to sound serious or jump on a wave of humor/sexiness to gain more followers? What ‘image’ do I want to portray?

In her book Doppelganger, Canadian author and activist Naomi Klein puts it like this,

We carefully cultivate online personas—doubles of our “real” selves—that have just the right balance of sincerity and world-weariness. We hone ironic, detached voices that aren’t too promotional but do the work of promoting nonetheless. We go on social media to juice our numbers, while complaining about how much we hate the ‘hell sites.’4

That digital self we construct will, of course, depend on what our aims are on the platforms we use — some people seek kindred spirits and want to show up as themselves as much as the virtual constraints allow, others hide behind anonymous accounts for either safety or to vent frustrations they don’t know how to deal with in real life.

Everything, however, begins with making that account and building that profile. Does this pile of pixelated ashes provide us the power to be reborn? To reinvent ourselves?

That metaphor neglects that only another phoenix can rise from the ashes. No matter how often it burns, the phoenix cannot escape itself. By either enhancing or obscuring parts of ourselves, we still take that ‘self’ as a starting point. We have no choice.

We are not phoenixes; we are personal brands.

Personal brands and main character syndrome

Let’s return to Klein’s Doppelganger. She writes,

… many of us have come to think of ourselves as personal brands, forging a partitioned identity that is both us and not us, a doppelganger we perform ceaselessly in the digital ether as the price of admission in a rapacious attention economy.

When I write for myself, I write as myself. But I am also writing as Gunnar™, the virtual version of me that hopes you’ll consider subscribing, liking, and sharing (nudge, nudge). I think, or at least hope, that the overlap between full, physical me and Gunnar™ is substantial at Subtle Sparks. I’ve mentioned before how, from a professional standpoint, this newsletter is not optimized for growth.

That wouldn’t be me. Which me, though?

The writing style, the topic choice, the sprinkle of personal reflections, the inability to resist wordplay… Sure, that’s all me. Yet it’s not all of me. Gunnar™ is still a redacted version. The shadows, the sharpness, and the insecurities that also make me me are not for public consumption. Careful readers will have seen flickers of them, I’m sure, but those are leaks rather than offerings.

Me, me, me — sounds like a guy on a first date. (I’m kidding, guys, relax. Everyone does it.) Ironically coined on social media, main character syndrome is the tendency to see your own life as a story with yourself as the main character and everyone else as NPCs (non-player characters, to return to the game theme). Think of TikTokkers who get annoyed when people walk through their shot in a public space or the fitfluencers who take up half the public gym with cameras and tripods so that their followers can see them perform a deadlift with dreadful form.

Like philosopher Anna Gotlib, I recognize and appreciate that stories and narratives shape our lives. They provide meaning and motivate us toward whatever goals we set for ourselves. By definition, the only point of view we can access is our own — we cannot help but see the world through our own eyes. But once that story begins to be shaped by an increasingly individualist society, it gets warped into a delusional hero’s journey that plays into our ego. To counter this, Gotlib suggests,

… sitting with our anonymity, solitude, boredom and lostness; pushing back on the equivocation between performance and authentic connections; making ourselves vulnerable to others, and thus to failure. It might mean seeing ourselves as always incomplete – and recognising that fulfilment might not be in the cards, that life is not a triumphant monomyth, and others are not here to be cast in supporting roles.

This advice is difficult to follow in an age where everything is posted on social media, where we are always ‘on’, where everything needs to be quantified, where our phones ping (or, more agonizingly, don’t ping when we want them to), and where we swipe, like, and comment with reckless abandon. While I am less negative about social media than some self-proclaimed pundits, I am critical about how it currently pressures us to position and perform as a personal brand in a popularity contest.

Beyond social media, many applications of technology aim to reduce friction, even in interpersonal relationships. Again, I am a big fan of technology in general, but when it chips away human-to-human contact, I both wonder and worry about the outcome. We order food with a QR code and use the self-checkout at the grocery store5. And that’s if we don’t order everything to be delivered to our doorstep.

Especially in jobs and interactions where human contact is important, this leads to what sociologist Allison J. Pugh calls ‘colliding intensification’. In her words,

A profusion of jobs has arisen in contemporary capitalism involving ‘connective labor’6, or the work of emotional recognition. Yet the expansion of this interpersonal work occurs at the same time as its systematization, as pressures of efficiency, measurement and automation reshape the work, generating a ‘colliding intensification’.

There is nothing intrinsically wrong with automation or efficiency, but let’s consider where we apply them. Little by little the drive to reduce friction is eliminating small day-to-day personal interactions. On public transport, we are glued to our tiny screens. In grocery stores, the only sound is a scanner’s beep-beep. Soon, AI bots will like AI-generated posts and we’ll get a little orgasmic jolt at the illusion of connection this provides. We curl around our screens as if their light gives us warmth while (most men) swipe until their thumbs give out or (most women) dodge dodgy DMs full of dick pics.

This aim for relentless, wholesale friction reduction glosses over the fact that you need friction to build a fire. As a phoenix from the fire’s ashes, I rely on Klein one final time to help me with the conclusion. It’s actually simple.

We were not, and never were, self-made. We are made, and unmade, by one another.

Thanks for joining me around this virtual campfire. Phoenix not guaranteed, I’m afraid.

If you think that’s impressive, let me introduce you to a recently discovered extinct species of ‘terror’ bird, possibly standing around ten feet tall, eating meat, and hunting in packs. These absolute units ate phoenixes for breakfast.

The few times I played RPGs, I always ended up with a gloomy, dark magic warrior elf dude. I wonder what that says about me.

And increasingly everywhere else online. Social mediafication affects more and more corners of the internet (hello, Substack Notes) and we’re gamifying many aspects of life.

Don’t even get me started on dating apps…

I am certainly guilty of this.

She explores this idea of connective labor more in her recent book The Last Human Job, which is playing hide-and-seek in my to-read mountain.

So many selves:

-Who we think we are

-Who we think other people think we are

-Who we want to be

-Who other people think we are

-Who we "really" are

Crikey!

Good writing Gunnar! Definitely not your average Substack (and that's a good thing!). 👏

Hear hear. 👏