Utopia

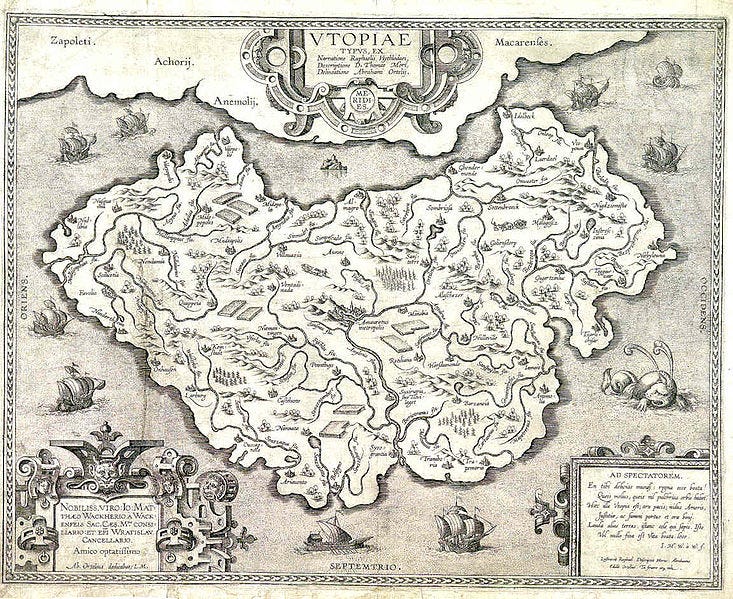

In 1516, Thomas More’s Utopia was published. Since then, the name of his imaginary island society has rooted itself firmly in our cultural conscience.

Utopia is, by definition, a fiction. Combining the Greek οὐ (not) and τόπος (place), utopia’s literal translation is ‘no place’. Since More’s day, however, we’ve been mixing utopia and eutopia (good place), so utopia today means not only a fictional place, but a good fictional place.

That ‘good’ part is not necessarily true for More’s utopia. The story's second part begins with all the promise the island society holds — every able-bodied person has work, no one works more than six hours per day, virtually no crime, free healthcare, freedom of religion, to each according to their needs, etc. But, we quickly learn that there are characteristics of the fairytale that don’t have quite the same uplifting ring. Strict population control, slavery, discrimination against atheists, and premarital sex is punished by enforced celibacy, to name a few.

Yikes.

Not a Eutopia then.

What point More tried to make with Utopia remains a topic of discussion. Was it a satire of Euro-Christian values (even though More was a devout Christian)? Was it a sleight at people who thought society could function without private property? Or was it an earnest examination of contrasting political systems?

The interpretation of historical sources is always a reflection of the present.

Likewise, visions of the future are reflections of the present.

Tech brotopia

Our present, though, is disproportionally shaped by a small group of people. Usually, people with a modicum of power. And people in power like to stay in power.

That’s why a lot of utopian visions - which have outgrown More’s representation - are often unimaginative, slightly shinier versions of the present. Visions of tomorrow look a lot like today, only with a bit of extra technological gloss. Maybe a few robots, self-driving cars, and fancy transparent do-all screens are invited too.

This popular brand of utopianism is called techno-utopianism and it’s usually part of a larger brand, TESCREAL — a term coined by computer scientist/ethicist Timnit Gebru and philosopher Émile Torres. TESCREAL is the acronym of a bundle of future-oriented ideologies: Transhumanism, Extropianism, Singularitarianism, Cosmism, Rationalism, Effective Altruism, and Longtermism. Gebru and Torres (vehemently) oppose the TESCREAL bundle, which they consider a thinly veiled excuse for eugenics and a privileged future for the few.

I’m not sure that lumping all these philosophies together is the most sensible approach, nor do I think that using it as a catch-all term to point an accusatory finger at people who align with one or more of these ideas is a great way to encourage healthy debate. (Note: I’m also not sure how much of a personal vendetta is going on with all this.)

There is one shared trait among TESCREAL and techno-utopian visions that warrants a quirked eyebrow: the idea that technology is the panacea that forges the future and carries everything along in its wake1.

I used to think that. I changed my mind.

Technology can enable progress.

But the true drivers of progress are people.

Omelas

A few weeks ago, Amazon head honcho Jeff Bezos caught some well-deserved flack for his vision of space colonies that could house trillions of people so that humanity could produce “a thousand Mozarts and a thousand Einsteins.” (This is something he’s been saying for several years at this point.)

I don’t mind the space colony part. In fact, give me all those O’Neill cylinders.

The issue - and the reason for the pushback on social media - is this: there are probably already dozens of Mozarts/Einsteins walking around; they’re being ground to dust in Amazon warehouses or working three jobs to pay rent2.

And that’s what most techno-utopians miss. We don’t need space colonies to breed3 more people in the hope that we crack the genetic code for genius by a brute force approach; we need the social conditions that allow brilliance to thrive, no matter what form it takes.

Imagine the utopias popular media tends to feed you. Pretty much today, aren’t they? With some shiny veneer, perhaps. But that way lies danger. As Silicon Valley bulldozes the planet into a wasteland of algorithmic injustice and an oil sheik led the conference that was supposed to tackle climate change, I don’t have to look far for examples…

In her cautionary tale ‘The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas’, Ursula K. Le Guin writes about the city Omelas, a utopia in all but name. The city has one dark secret, though. Its existence hinges on a child imprisoned in a dark, dirty dungeon beneath all the splendor. Each citizen of Omelas is eventually told the truth and yet, most of them choose to stay. Change is hard, after all. A few leave. Le Guin finishes the story with the unknown fate of the leavers:

The place they go towards is a place even less imaginable to most of us than the city of happiness. I cannot describe it at all. It is possible it does not exist. But they seem to know where they are going, the ones who walk away from Omelas.

They might be walking toward Protopia, a relatively new word coined by author and tech thinker Kevin Kelly in 2009. While it has as many meanings as proponents, Protopia is a more pluralistic vision of the future that seeks to avoid the inherent dichotomy in the idea of utopia (a utopia for some is a dystopia for others). The details, if any, of Protopia are sketchy, but one thing that sets the different visions of Protopia apart from the utopias we’re fed is that a protopia tends to start from people and social changes to guide the application of new technologies.

And that is the problem with utopia: A better future is not programmed top-down; it grows bottom-up.

I’m using a bit of a black-and-white shortcut here to get to my point. Of course, techno-utopian visions are not (completely) blind to the importance of social structures. It’s more about the emphasis on technological versus social change.

Not to mention that Mozart probably piggybacked on the musical prowess of his prodigious sister Maria Anna Mozart, affectionately known as Nannerl.

I use this word intentionally. For some reason, a rather disproportionate number of billionaires seems to see the rest of humanity as a teeming mass of cattle to be used and exploited. (Too cynical?)

Very well written!

Indeed it must start with people, unless we want to create a ‘robotopia’ of course...

The first piece I published touches on much the same topic. I hope you don’t mind me sharing it here:

https://open.substack.com/pub/thescrawnyape/p/a-toolmakers-dream?r=392lqs&utm_medium=ios&utm_campaign=post

What a great piece! And what a frightening proposal from Bezos... the tech bros look at the entire humanity and universe as something to be made more (and more) efficient. I want to run away in the opposite direction.