Talking Animals and Non-Human Consciousness

A story of elephant names, whale songs, and the null hypothesis

Sing my name

On June 12th, 2013, Victoria died at 55 years of age.

Her son, Malasso, aged 13, tried to rouse her from this unexpected sleep. Daughter Noor, aged 10, cried heavy tears. In the days following her death, extended family and acquaintances showed up to pay their respects. Victoria was well-known and well-liked.

She was also an elephant matriarch.

Did the other elephants mourn her passing? Did they grieve?

For a long time, the standard answer in ethology (the science of animal behavior) would have been a resounding ‘no’. The idea was that we shouldn’t transplant human emotions onto animals and that seeing animals through a human lens was non-scientific. Even before ethology became recognized as a separate discipline in the 1930s, British psychologist Conwy Lloyd Morgan wrote in 1903:

In no case is an animal activity to be interpreted in terms of higher psychological processes if it can be fairly interpreted in terms of processes which stand lower in the scale of psychological evolution and development.

This has become known as Morgan’s Canon and it reflects Descartes’ earlier assertion that animals are biological machines lacking any interiority.

The recognition of (potential) subjectivity in animals is changing, not in the least thanks to the work of Jane Goodall, Dian Fossey, and other (mostly female1) researchers who - gasp - named the animals they observed and attributed emotional states to them. Morgan’s Canon is stubborn, though, and persists2.

One of the reasons Descartes thought animals were biological automatons is because he didn’t think animals had language. In his Discourse on Methods (part V), he compares humans to non-human animals and writes,

… they could never use words or other signs arranged in such a manner as is competent to us in order to declare our thoughts to others.

Isn’t this a coincidence… Recent research suggests that elephants use individually unique calls to address each other (names?) and that the songs of sperm whales,

… are more expressive and structured than previously believed, and built from a repertoire comprising nearly an order of magnitude more distinguishable codas. These results show context-sensitive and combinatorial vocalization…

Oh, and let’s not forget our feathered friends. Carrion crows are capable of symbolic recursion. As in, they can ‘nest’ symbolic elements in others — like how you can combine simple sentences into a complex one; an ability once thought to be one of the unique characteristics of human language3. Turns out carrion crows do this better than non-human primates and give human children a run for their pocket money. Only months ago, researchers found that these same crows count out loud at a level that “is challenging even for young humans.”

Is this as complex as (adult) human language? No. Or, not as far as we know.

Bouba? Kiki? Where language meets thought

What does the word ‘bouba’ feel like to you? Soft and round? Cuddly, perhaps?

What about ‘kiki’? Sharp and pointy?

This is known as the - you’ll never guess this - ‘bouba/kiki effect’ and it is found across cultures and writing systems. Maybe across species boundaries too. A recent preprint finds that chicks (as in baby chickens) are also sensitive to the bouba/kiki effect!

Together, bouba and kiki suggest that there are some near-universal patterns of sound-shape matching. These universal patterns appear to run counter to the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis4, also known as linguistic relativity, which claims that the structure of a language influences its speakers' cognition and worldview. This hypothesis comes in two forms:

Strong version (linguistic determinism): Language determines thought.

Weak version (linguistic relativity): Linguistic categories and usage influence thought.

The strong version is generally discredited, but the weak one has evidence going for it. Language shapes how we see colors and experience space and time. The gender of nouns in gendered languages also affects our perception, as does whether we use active or passive verbs — a sad example is that the passive verbs news outlets use to describe violence against women make people perceive it as more acceptable. And here’s a fun morsel for my fellow bilinguals: not only does bilingualism make us conceptually flexible, it also (literally) rewires our brains.

I don’t think bouba/kiki and Sapir-Whorf need to be at odds, though. The first is about sound and shape, the second about content and meaning.

I’ll take my cue from our corvid pals from earlier and rearrange the ideas as follows: we can rearrange universal sound-shape connections into different elements of different languages, which then feed back to us and (re)shape our perception5.

That sounds like abstract sleight of hand (or tongue?). The point is simply that when we witness, or participate in, an exchange with complex language, we assume we’re observing a twisted loop of sound, content, and, perhaps, consciousness. Since we often use language as a social cue, the closer the language of others resembles ours, the more we think they are part of our strange loop.

What about non-human animals6? Or AI?

Non-human animals are (not) like us

In a recent paper, philosopher Kristin Andrews asks us to start from the assumption that all animals are conscious and then figure out how they are conscious, rather than assume that animals are not conscious until they prove otherwise.

This makes sense.

Unless you believe that, at some point, humans were the sole recipients of the consciousness spark through some divine intervention, our shared evolutionary history with non-human animals may very well include the building blocks of consciousness. Also, we (for now?) ‘test’ consciousness with markers based on the human experience. But who says that our type/degree of consciousness is representative of all possible forms of consciousness?

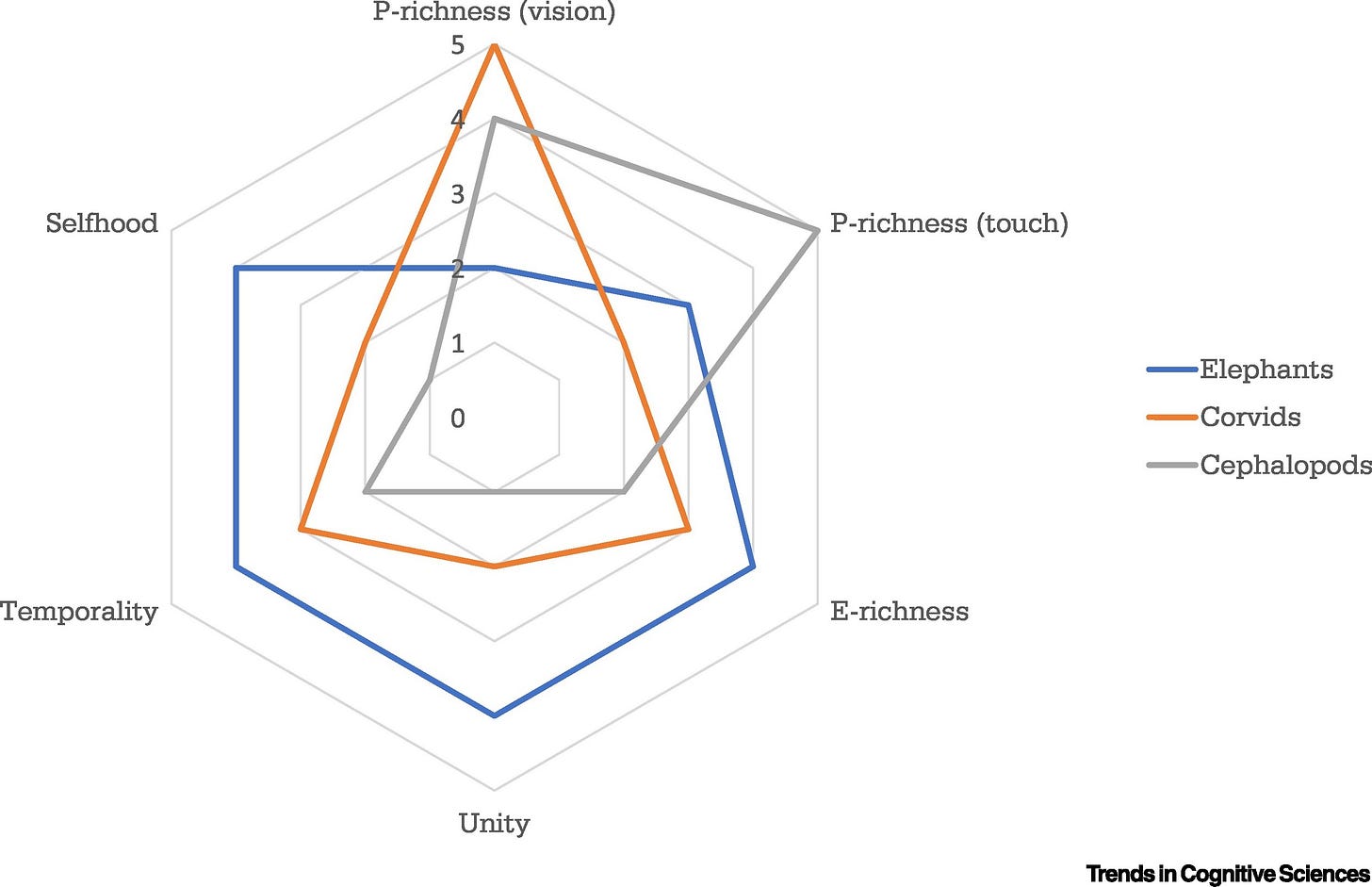

A first step in the direction of evaluating consciousness as a multidimensional phenomenon is this study that makes the different dimensions explicit. In 1,000 words:

Of course, there’s still debate about which dimensions to include. For example, some researchers suggest ten rather than the six above.

Did you notice language isn’t on the list?

That’s interesting because a significant proportion of non-experts attributes a possibility of consciousness to large language models (LLMs) for no other reason than that their use of words mimics ours. There’s a long history behind denying that animals have anything resembling our consciousness until they convince us. At the same time, we seem (overly?) eager to give LLMs the benefit of the doubt. Language is not enough; the intent behind the language matters. And that intent may be communicated in many ways, including ways we are less familiar with. In LLMs, our reasoning flows backward. We see language, so we assume intent.

As I’m about to click ‘publish’, I come across a study suggesting that deep learning can enable acoustic individual identification, or the recognition of individual animals based on their vocalizations. Their voice, if you will. This fits within a larger effort - see the Earth Species Project - of (potentially) decoding animal language with AI. For example, remember the whales we met at the beginning of this post? The study that found the ornamentation and rubato in their songs used machine learning…

That seems (sounds?) fitting to close the twisted loop of this essay.

I hope you found a few interesting ideas in today’s post. If you enjoyed it and appreciate the work behind it, click hearts and buttons and share it to appease the algorithm.

As always, thanks for stopping by,

Related thoughts

This is something I’ve been rabbit-holing for a while. I've alluded to it in my alpha male debunking, but we’ve known for quite some time that (most) male researchers often unwittingly impose the ‘male default’ on their observations of animal behavior and ecological interactions (and in many other fields).

Fun story, I did my PhD on animal ‘personality’, and I had to be quite careful about how I framed that because the term alone was enough to raise some reviewer hackles.

Yes, this is a complex sentence.

This hypothesis is the crux of the first-contact movie Arrival, based on Ted Chiang’s short story ‘Story of Your Life’. (Also, Newspeak in Orwell’s 1984.) If you don’t know Chiang, go read all his stories! Remarkably in this age of content overload, he has published 18 stories - including many award winners - over a career of almost three decades and is (rightfully, in my opinion) considered one of the finest short story writers of our age.

Though I’d be happy for any linguist to weigh in and set me straight.

Especially, what about those who don’t rely on vocalizations as their primary mode of conversation? When an octopus lets colors and shapes ripple across its skin, are you more likely to assume intent or instinct? Here’s a whole post on the dreams of octopuses. Hey, look, another book recommendation. Ray Nayler’s The Mountain in the Sea is a near-future thriller about first contact… with an octopus species that (may have?) developed its own language and culture.

Since you are interested in whale consciousness, AI, and are a fan of Ted Chiang, you also need to check out Adam Nathan’s remarkable serialized story Moby. The first part is here, and you can use that to get to all the rest of it:

https://www.adamnathan.com/p/5-moby-june-2024-part-i

I was just having this conversation with my best friend about how much I can’t stand when some form of the argument that humans are unique among animals (read: superior) because of how our minds work appears—which means I’m annoyed a lot, because it’s everywhere! It’s based on so many arrogant assumptions, some of which have been disproven. Carl Safina’s Beyond Words really articulated this idea beautifully and is one of my favorite books.

I love love that you’re exploring that here, and I’m glad to have found your substack. Thanks for the wonderful take!