Spiders in Space and the Meaning of Life

The International Space Station, Hannah Arendt, three anchors of meaning, and social media webs

Spiders… in space!

Not too long ago, we launched Mozart into space, but have you ever wondered what happens when you put spiders in a spaceship1? We actually know, because… science.

A 2021 study followed the adventures of two golden silk orb-weavers (Trichonephila clavipes) — expert web-builders — that were invited to the International Space Station. Two words: wonky webs.

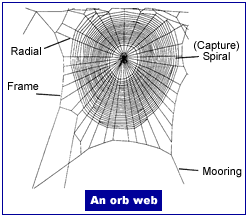

A lot of spider webs2 are asymmetrical. The web’s hub, where the spider lingers, is generally higher up. And, sitting there, the spider almost always looks down. The reason is simple. Gravity. It’s easier to run fast toward a prey that is struggling to free itself when you’re going down and gravity gives you a little extra oomph.

But what happens when we take that grounding gravity away? In the ISS, the spiders' webs were more symmetrical than those of their earthly cousins. However, when the lights were on during the building phase, the webs were more asymmetrical (earth-like), with the hub closer to the light. In the dark, the newly built webs were more symmetrical. The spiders, in other words, use the light as an extra engineering cue.

There is a lesson about the meaning of life in those spiderwebs.

Webs of meaning

Humans, after all, make webs too. Not with silk, but with connections.

In The Human Condition, philosopher Hannah Arendt uses the term ‘web of relations’ as a metaphor to show how our acts and words bind us together.

I hope Arendt won’t mind that I take the metaphor a bit further. It’s what I do. Anthropologist Robin Dunbar estimated that, on average, our individual webs of relations contain 150 people. Like any good web, our web has spokes (or radials), frame threads, mooring threads, a spiraling capture thread, and the hub.

In our extended metaphor, you would be the hub and the spiral threads are the people you know. Lover/partner/kids would be in the first spiral, close relatives and very close friends would be in the second, regular friends in the third, acquaintances in the fourth, and so on. The radials that connect the spirals are what you bring to each level of relationship; who you are as a partner, a friend, etc. The frame threads keep the web together — time, environment, health, resources, effort…

Today, let’s consider the mooring threads that anchor the web. Without anchors, the web would be lost, blowing away in the wind. Anchors are individually unique and they determine the location and shape of your web. The anchor points are the meaning of life; they provide a foundation for you, for your connections, and for your place in the world. A recent review study on the subjective meaning of life suggests that our webs have three anchors.

Coherence, or “the perception that one is able to make sense of the past, present, and imagined future aspects of their life and integrate their life story into a coherent whole.”

Purpose, or “the feeling that one's behavior is guided by personally valued goals.”

Existential significance, or “the extent to which a person believes their life counts—i.e., that their existence has and will have a lasting impact on the world.“

There we go. The meaning of life, solved. Subscribe, please.

If only it were that easy. (I still think you should subscribe, but I’m biased.) How do we spin the mooring threads that give us those anchors? A relatively new approach, which suits the web metaphor, is called ‘life crafting’ and can be summarized as: Define your values and passions, reflect on your current and desired abilities, social life, and career, imagine your ideal future, break it down into specific goals, and make a public commitment to those goals.

It almost - almost - triggers my self-help allergy, but each of these steps has some scientific backing. We like a trajectory with challenging but achievable sub-goals (did someone say gamification?). It’s hard to find meaning if you don’t know what matters to you and it’s hard to find meaning if you know what matters to you but you don’t move toward it.

For many of us, the gravity of social expectations and the presence of nearby webs determines where we start spinning the silk of meaning. And yet, sometimes those webs feel… off; shivering in the cold wind of self-doubt, the silk crackling with the paralyzing frost of emptiness.

Can we take our cue from the spaceship spiders and move closer to the light as an alternative?

Blinded by the light

Spiders change their webs in space. So what happens when we extend our personal webs of meaning into a new virtual environment? Do we reorient our meaning-making closer to the light of our ubiquitous flickering screens?

Since the advent of the internet, and especially forums and social media in the early 2000s, we suddenly find ourselves entangled in yet another web. This social web was first mentioned in a 1996 interview with writer and cultural critic Howard Rheingold. The internet, he thought, would become the home for a manifold of online communities. A social web.

If I were to believe much of what I read on Substack, many people are here ‘to find a community’. Finding an online tribe can be meaningful. It might provide coherence (being part of a group of like-minded individuals), purpose (supporting other writers and online friends, becoming a better writer), and even a shield against the throes of existential despair (by being listened to, connecting with kindred spirits, or having a place to go with your worries). This is the ideal scenario, of course, but some research suggests that even memes can beneficially affect meaning-making — mediated eudaimonia, the researchers call it. Here, have some eudaimonia.

Interestingly, our social webs can differ on different platforms. For example, a 2018 study on social media use in young adults found that,

WhatsApp is a multifaceted communication domain; Facebook is a space for displaying the socially-acceptable self; Instagram is an environment for stylized self-presentation; Twitter is a venue for information and informality3; and Snapchat is a place for spontaneous and ludic connections.

That sounds… exhausting. Building and maintaining webs of connections is cognitively and emotionally demanding. Perhaps this overload of virtual webs is one of the roots of the current wave of social media fatigue that hits so many of us. As we are forced to maintain webs in a shattering social media landscape, are we stretching ourselves too thin across different platforms? Each virtual web is made of tentative and tenuous silk. While online connections and parasocial relationships can be very real, they contain an (even more) edited version of ourselves and the threads often lack the many non-verbal cues that help us connect.

Can we manifest those virtual webs physically and turn strings of code into threads of real-life connection? Can we give the light of our screens the gravity of meaning?

We’re certainly trying. On Substack, for example, writers in larger cities organize meet-ups that allow writers to move beyond the chats and posts. Another example are my good friends the dating apps4 (sarcasm overload). In 2010, an essay in The Economist (with the great title Love at first byte) quoted psychologist Dan Ariely, who already noted that dating apps and sites,

… treat human beings as if they are goods that can be fully defined according to a set of standard attributes, in much the same way that, say, a digital camera can be described by the number of megapixels that it has and other characteristics. But this cold, drearily functional approach to assessing compatibility fails to capture the indefinable spark that triggers romance.

In the same essay, anthropologist Helen Fisher notes (correctly) that we often choose potential partners who are similar to us in background, values, and - yes - even appearance. Dating apps simply help us narrow the pool5. Yet even she agrees, that,

… there is inevitably some magic to love

Magic? It’s biology all the way down (says the biologist), but we still don’t have the full picture of how the objective phenomena that underlie subjective experiences, like love, actually work. It’s a pretty hard problem.

Machine learning is getting better at mimicking chemistry on a screen. But, so far, we need experimental validation of what the computer models come up with. Likewise, people can build chemistry online. Yet, we (maybe?) still need in-person interaction to ‘validate’ the screen chemistry in real life.

Sometimes, you come across someone who is the perfect partner on paper (or on the screen). You start dating and… it just doesn’t work. This does not imply that you need to be swept off your feet on the first date — that goes bad as often (or more) as it turns out well. Strong love can grow over time. But there is a spectrum from ‘I can tolerate this person’s presence’ to ‘I want to rip their clothes off here and now’. For a long-term partner, somewhere in the middle, with decent leeway for different contexts, is probably a good starting point.

Some things belong in the virtual web, others in the physical one. The decision about which online threads can be transplanted to the IRL web requires real-life context.

To build a sturdy web, physical or virtual, you need the anchor threads, but without the rest of the web, the anchors are pointless. You define your meaning of life, but it only becomes real through interaction with others.

You are a hub for yourself and you are a thread for others.

I hope you find your anchors.

Thanks for sticking around in the silk of my writing. If it meant something to you, consider liking, sharing, and so on. It helps me add threads to Subtle Sparks’ web.

I must mention the brilliant science fiction novel Children of Time by Adrian Tchaikovsky here — a far-future story with, yes, spiders as some of the main characters. Also, a book in which the actual biology of spiders is used to depict how they interact with the world.

Biology bonus: Spiders don’t simply make webs to hang around in, they can spin one around their own abdomen as a cocoon for their offspring or use light spider silk as a balloon to fly around with. Some spiders are more active hunters that use webs as ‘nets’ like arachnid gladiators. The webs, in their many forms, are not only marvels of engineering, but also of materials science. The spider silk of different species differs in properties, but it can be up to three times tougher than Kevlar and five times stronger than steel. Add to that that it’s flexible, water-soluble, biocompatible, and biodegradable, and you’ve got a miracle material for things as diverse as armor, running shoes, and surgical thread.

This was pre-X. Oh, how times have changed.

Ironically, by providing a pool that is way larger than the one we would have otherwise swam in.

I enjoyed this. Your discussion of the various social media platforms made me think of the different stages we perform on in physical life. Our behaviour in Church is different than how we conduct ourselves in the workplace and in the bar at half-past midnight. These platforms all serve a unique purpose in expressing our myriad of personalities. No wonder Authenticity is hard.

Thanks for an excellent post!

I think meaning of anything is always coming from outside, like the meaning of a chair is not in the chair but in a way human or a cat uses it.

Same is with meaning of human life- it’s outside of it. Since we all interconnected and there is really nothing outside people and their relationship, so the meaning of a single life comes from the network.