Dunbar’s ballpark

The number 150 might seem like nothing special to you, but the ears of every biologist and psychologist just perked up.

150 is Dunbar’s number, first articulated by anthropologist Robin Dunbar in the early 1990s. By looking at primate brain size and social group size, he concluded that human brains are most suited for social groups of around 150 individuals1. Of course, the number is a ballpark; an extrapolation based on a correlation. And sure, the human brain might simply be a linearly scaled-up primate brain, but Dunbar’s number has been disputed several times. Many factors beyond social organization determine brain size. Chimpanzees, gorillas, and orangutans have roughly similar-sized brains. Yet chimps live in fission-fusion groups of (usually) several dozen members, gorillas in harem-style groups of maybe ten individuals, and orangutans are widely known as relatively solitary primates2.

Still, estimates of a ‘natural’ (quotation marks matter) human group size settle on a range from a few dozen to a few hundred, so Dunbar’s number is a decent ballpark that has already carved its niche in our cultural background noise. Let’s roll with it. After all, constraints on time and working memory imply that we probably won’t be able to maintain meaningful relations with thousands of people.

Hold on.

Hello, internet.

Tribe me

Whatever the value of Dunbar’s number, the human brain is primed for living in group. So much so that not living in group has plenty of detrimental psychological and physiological effects. Even the most solitary among us (why’s everyone looking at me?) have to admit that one of their most profound (though perhaps unspoken) wishes is ‘to belong’3.

Thank goodness we can now cycle through dozens of pseudo-social interactions with strangers every day. Ha, sarcasm. Don’t misunderstand me, I think that online interactions can certainly be a way to ‘find your tribe’, but we must be careful not to think that a click, like, or swipe is the equivalent of an actual meeting or conversation. At best, they can be the starting point for a connection. At worst, they are troll food.

Unfortunately, some people take advantage of our need for belonging and the internet is, sadly, a great place to do that. Once you stumble into a tribal rabbit hole, your newfound fake tribe encourages you to share and otherwise boost information that confirms its tenets. Consider this 2023 study, which suggests that the most pressing reason for people to share misinformation is not that they actually believe it, but to avoid the social cost of not sharing. AKA being cast out of the tribe.

This is not to say that tribes are bad, but to note that not all tribes are the same. There are organic groups of like-minded people who both accept and challenge each other and are open to different opinions and lifestyles (probably good) and there are engineered tribes that want to enforce rigidity and obedience (probably not good). Or, as this chapter in the book Deterrence in the 21st Century puts it:

While tribes are relational and emergent in their scope and scale, they are often cast in the same light as engineered populist movements that generate hatred and othering to increase fear, resentment, and contestation... Organic tribes, on the other hand, are a relational and network-based grouping of like-minded people seeking ontological security to assuage a growing sense of uncertainty in an ever-globalizing, placeless lived experience.

Simple as one, two, three?

Once upon a time not too long ago, you were born, lived, and died in the same village. For many people, that is no longer true. Many of us4 are now in the paradoxical situation where we are freer than ever to find our tribe but also have difficulty doing so because we’re no longer dropped into it by birth and (to some extent) location.

Some people are good at it, though, finding their organic tribe on- or offline. How? Honestly, I’m the wrong guy to ask. Let’s look at some research instead. ‘Belonging’ is notoriously slippery to define, but this 2021 review provides a valiant effort:

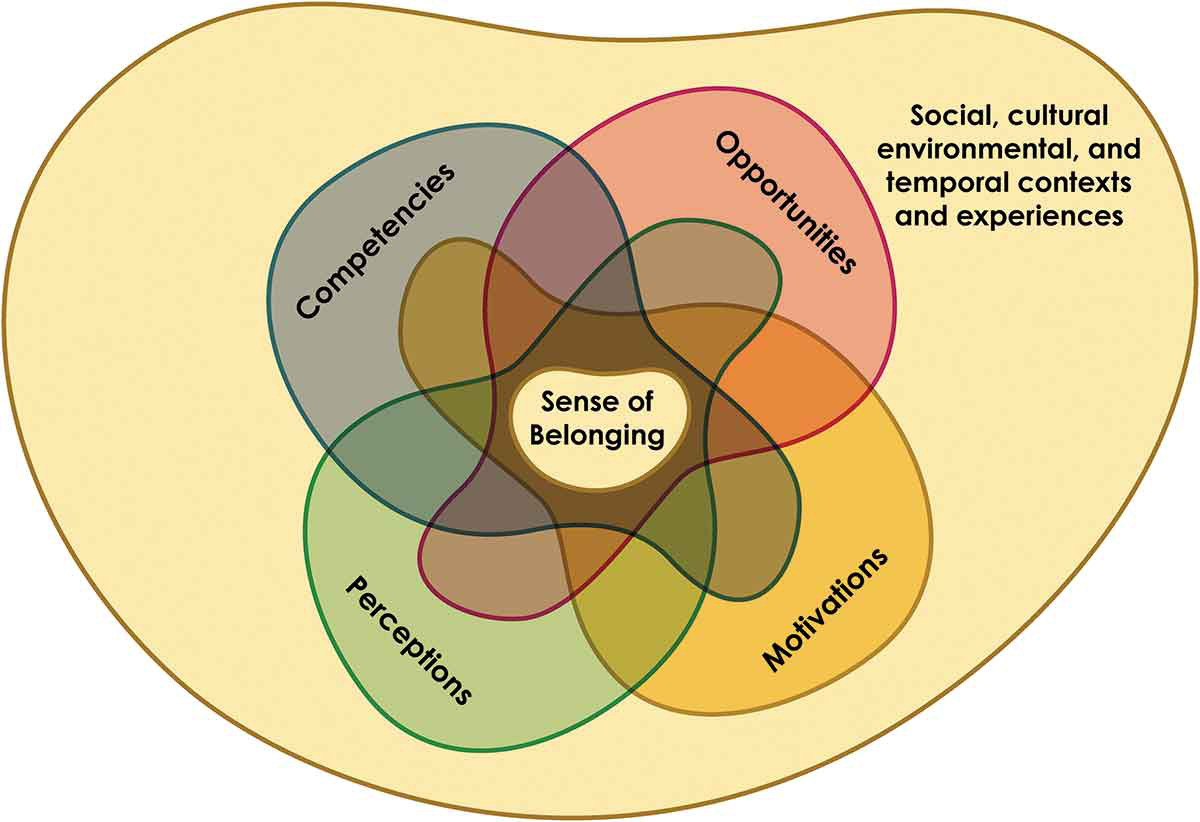

… belonging is a dynamic feeling and experience that emerges from four interrelated components that arise from and are supported by the systems in which individuals reside.

What are the four components of that fuzzy feeling called belonging?

Competencies: being good at relating to people, and at being relatable.

Opportunities: the chance to run into people to connect with.

Motivations: wanting to belong somewhere.

Perceptions: how you subjectively evaluate your ‘fit’ with a potential tribe.

I’d argue that a motivation to belong is near-universal in humans (see all the above). Check.

Perception can be distilled into ‘when you can be a significant enough chunk of your full self and feel accepted’. Check.

The other two I find trickier because they don’t only depend on you. For the opportunity, where do you meet the people you want to connect with if you haven’t met them yet? Common advice is to go to places (irl or online) you’re already interested in. That common interest might then be a starting point for a connection. Good, but not good enough. A common interest is a ‘nice to have’ in a friend- or other relationship, but not a ‘must have’ or ‘enough to have’.

There has to be, I think, a deeper sense of compatibility. Of character, perhaps? Of values? This brings us to the final, and possibly hardest, part: the competencies for making the connection. For some people, this seems to come easy. Yet, I think there is a difference between being good at connecting to a lot of people and making the right connections. You don’t need to be a social butterfly to find a tribe. Being genuinely curious about people without being intrusive is a good start. When that interest is reciprocated, there’s potential for connection. That potential connection becomes real when you find that the earlier-mentioned compatibility is present. When someone (or someones) just get(s) a part of you most people don’t, that is an amazing feeling.

Easier said than done.

I know.

Thanks for stopping by and taking the time to read my wandering thoughts. It is appreciated!

Dunbar’s number is actually 148, but big error bars and - perhaps - a keen sense of marketing led him to settle on 150.

Notoriously clever apes too. Only weeks ago, a report on the male orangutan named Rakus suggests that orangutans join a select club (humans and chimps) of animals known to engage in ‘active wound treatment’. After sustaining a facial wound, Rakus purposefully chewed leaves from a liana known for its pain- and fever-suppressing qualities so that he could apply the sap to his wound and then he used intact leaves as a wound dressing.

To clarify: solitude is not equal to loneliness. You can be lonely in a crowd and at peace in solitude. Also, some people may have gone through things in life that make them decide they’re better off alone. I question that decision, but it might be that in some (very rare) cases this is indeed true.

I understand this is a privileged perspective and culture, network, and resources will - to differing degrees - limit each of us in how free we truly are to find our tribe.

Nice post - heard of this magical 150 number before. No wonder big cities like London can feel a tad unfriendly and overwhelming. I just subscribed for more insights.

This is an important article because it gives us a missing piece of the puzzle of why civilizations collapse. Professor Dunbar has given us the most stable group number or congregation possible conducive to harmonious living and sharing. Yet we live on a planet of 8 billion. This is like saying the most stable form of uranium is 238, but what if we add a proton or minus a neutron-what then? The great mystery of the Bronze Age collapse is just that-it happened suddenly. Was the collapse due to Dunbar’s numbers and by adding language we also add the ability to increase that number dramatically, and by adding diversity, we increase that number much further, until we hit a tipping point called the “babbel capacity” beyond which the entire cultural enterprise collapses. What influences the babbel capacity? Diversity, tolerance, free trade and skill set training, religious freedom and much more. Underneath Dunbar’s number is the zeitgeist that supports the cognitive heuristic that took us out of the jungle and forged our cultural enterprise.