Farming spiders

Humans began farming roughly ten to twenty thousand years ago (with some smaller-scale experiments before that). The evidence so far suggests that, around ten thousand years ago, agriculture arose independently in different locations. Grains in the Middle East, rice in China, potatoes in South America, maize in Central America, and sorghum in Africa. Beyond plants, humanity domesticated and farmed animals like cattle, pigs, llamas, and alpacas around the same time, give or take a few thousand years.

Amateurs.

Ants have been farming fungi since long before humans existed, dating back at least to the dinosaur extinction sixty-five million years ago. Several ant species keep livestock as well, treating aphids as little cows. The ants provide protection and in return, they ‘milk’ the aphids with their antennae until the aphids secrete sugar-rich honeydew from their butts.

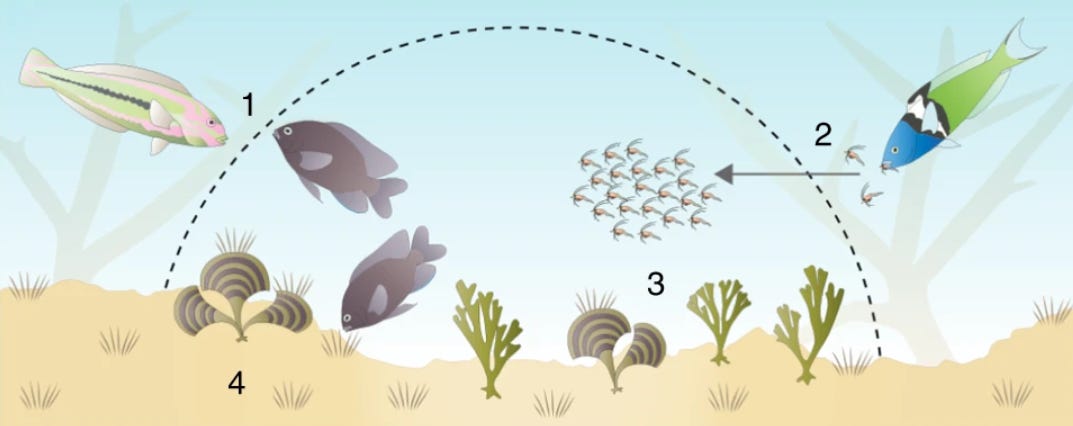

Ants aren’t the only animal farmers. Termites and ambrosia beetles also cultivate fungi. Longfin damselfish tend to algae gardens. These fish have even domesticated shrimp in their gardens so that the shrimp waste can fertilize the algae.

Even in the deep sea, which (at first glance1) seems to be a low-productivity ecosystem, we find animal farmers. The hairy claws of the wonderfully named Yeti crab aren’t just a fashion statement; they are used to farm nutritious bacteria. The crabs even wave their claws to help their bacteria get enough food.

New research has found another deep sea farmer: sea spiders2 of the genus Sericosura. These beautiful nightmare wanderers farm bacteria on their exoskeleton.

These sea spiders live along methane seeps in the Pacific and they ‘farm’ methane-eating bacteria. When they eat the bacteria, the sea spiders (indirectly) feed on the methane. The researchers call them the “methane-powered sea spiders”.

If you think that’s scary, wait until I tell you about what humans want to do to the deep sea.

Mining oceans

Traces of metals such as iron, manganese, nickel, copper, cobalt, and zinc sink to the bottom of the ocean (or they are squirted out of hot springs). Sometimes, those metals precipitate around a nucleus, which can be anything from a rock fragment to a shark tooth. Add a few million years, and this process leads to polymetallic nodules, or chunks of rare and/or industrially valuable metals (and rare earth elements such as molybdenum and yttrium).

Rare? Valuable? Smells like profit.

Ooh, let’s send big, clunky machines to the bottom of the ocean to trawl through sensitive ecosystems and suck up those nodules (and everything else).

This, in a nutshell, is the current state of deep sea mining.

While deep sea mining is only now taking shape as an industry, there were some trials in the 1980s. Back then, the efforts of scaling up weren’t worth the costs. By now, our resource hunger has caught up with us. Combined with new technologies, the prospect of sucking the seabed dry sounds more appealing (to some people). However, based on one of the initial trial runs in 1979, we know that the negative impacts on the ecosystem and biological communities last for decades.

One of the most popular target zones for deep sea mining is the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ)3 in the Pacific, with many billions of nodules ripe for the picking.

orac extti, which can be summarized as:

Eating planets

Imagine…

Humanity figures out interstellar travel. Physicists in a nondescript military lab bend spacetime into a pretzel that allows spaceships to waltz across previously impossible distances. Warp drive, wormhole, whatever floats your space boat. We can finally discover why no one rang Fermi’s galactic doorbell.

With this technology, a new industry is born and, under the guise of exploration, one of the spacefaring companies stumbles across a jungle moon. On this moon, the exploratory drones find an incredibly rare element. Let’s unimaginatively call it unobtanium. Giant machines will raze the beautiful extraterrestrial jungle. You know this story. Add (equally unimaginative) blue human-like aliens and you basically have the plot of James Cameron’s Avatar4.

Transplant the plot back to our own pale blue dot and you basically have, well, fossil fuel extraction, deep sea mining, intense large-scale agriculture, and so on.

Extractivism is the economic model built on the process and practice of extracting (often non-renewable) natural resources without regard for the impact on people and the planet. The concept of extractivism, even though it runs through human history like an STD, was only coined in 1996 to describe the for-profit exploitation of Brazilian forest.

In short, extractivism is how to eat a planet. You simply suck it dry. You see it not as a home or habitat (or spaceship), but as a pool of resources to strip down to its barest bones. Fortunately, planets are resilient. Unless we literally deconstruct Earth into building blocks for a Dyson sphere, our planet will be fine. The life on it, that’s another story.

Extractivism, by its nature, is a short-term profit-driven strategy. You grab what you can as fast as possible. You burn down a forest to plant crops. You destroy the deep sea to get metals and rare earth elements. You extract fossil fuels to put them in barrels and stockpile them while screwing the global climate. In the short term: profit. In the longer term: collapse.

This is not a plea to return to some imaginary pre-industrial Eden. There has never been such a place. Individuals, species, and civilizations require resources, and humanity is a hungry species. But extractivism is only one strategy to acquire resources, and it’s a bad one. Whether it’s the Na'vi in Avatar or one of many indigenous cultures5 on Earth, there are strategies to gather resources that look beyond the next election cycle or quarterly profit report.

Of course, regional initiatives are not easy to scale up in defiance of a global system with tentacles strangling many aspects of our lives, as noted by this paper that looks at possible alternatives to global extractivism:

Many of these initiatives searching for transformative alternatives acknowledge that it is difficult to achieve significant changes in global extractivism through minor transitions that do not alter wider sociopolitical structures…

So, I do not have the answer. I do not know how to stop humanity’s short-sighted resource gluttony6. But, whatever alternative emerges - and it must, because extractivism is, by definition, not sustainable - I think it needs (at least) these three characteristics:

Pay attention to direct and indirect effects, both in the short and longer term.

Recognize the connectedness that threads through life and non-life. Food webs, species interactions, geochemical cycles, climate effects…

Prioritize sustainable resource use, regenerative practices, and social effects over immediate profit.

Maybe we should learn from animal farmers…

Thanks for joining me to the deep sea, the richness of our planet, and on a brief sojourn on a spaceship to a Dyson sphere. If you enjoyed it, clicking buttons helps to keep me going.

There are several spots on the ocean floor, such as hot springs, that are remarkably biologically productive.

Biology lesson: Despite their name and appearance, sea spiders are not spiders. They’re not even arachnids. Evolutionarily speaking, they’re a sister group to arachnids and horseshoe crabs.

The mining areas in the CCZ are frequently visited by whales, whose songs might be muted by the noise of mining equipment.

Turn it into a desert planet and you have Dune. Extracting resources from a planet until it croaks or collapses is a popular science fiction trope.

One example is seven generation sustainability or the seventh generation principle, possibly originating in the Iroquois’ oral constitution, which mandates that important decisions need to take into account the effects on the seventh generation to come, aka roughly between 150-200 years in the future.

Another science fiction trope is the post-scarcity society in which material needs have been solved for everyone. Iain Banks’ Culture series is a great example of this. Oddly, fewer and fewer current science fiction books seem to take this starting point. Must be something in the water of contemporary world politics…

The ecology of Dune never worked for me. No primary producers. I'm surprised Liet-Kynes never noticed this!