Spaceship Earth

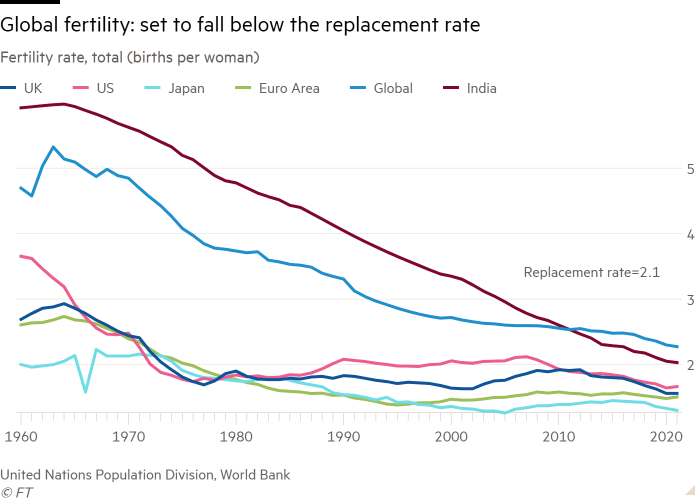

Recently, a shiver of concern rippled through popular media. We’re not having enough babies. So says a report in the medical journal The Lancet. By 2100, 97% of countries will have birth rates that are too low to maintain their current population size. Elon Musk is worried, and he urges people to have more kids — he’s doing his part with 11 children (so far?).

But let’s take a step back. Farther. A little farther still. Little more.

There, take a look now, at Sagan’s pale blue dot, our planetary home.

Already in 1879, American economist Henry George explored this zoomed-out perspective in his treatise Progress and Poverty. He saw Earth as:

… a well-provisioned ship, this on which we sail through space.

The issue with a spaceship, though, is that it can only carry a limited crew and, as Earth Overshoot Day illustrates, the human crew of spaceship Earth is going through its rations with alarming speed.

In ecology, carrying capacity reflects the maximum population size that can be sustained in a specific environment. Think of it as the crew capacity of spaceship Earth. But how many people can our planet support? The answer is far from simple and relies on assumptions about the level of technology and living standards. As you can imagine, estimates for Earth’s carrying capacity for the human species vary wildly — it’s an equation with many ball-parked variables. Recent work that includes measures of biodiversity and human well-being ends up somewhere between two and three billion people. That’s generally the lower end of estimates, but still, a slight majority of studies suggest less than eight billion. Guess where we are today? Yep, we left eight billion in the rear-view mirror a while ago.

With estimates that, with a few notable exceptions, range from a few to a few dozen billion, it’s clear that carrying capacity is not a fixed number. If the environment changes, or if we get better at extracting resources (or exploiting new ones), the number changes. We can’t deny that, currently, human (over?)population is involved in global challenges such as climate change, biodiversity loss, resource depletion, and so on. Part of me wonders whether Marvel’s Thanos may have had a point. In a way, he was thinking like a population ecologist. If we wipe out half of all life, would the remaining half be better off?

Gloomy, I know.1

Yet, in the spaceship Earth view, is the declining birth rate that bad? If there are too many people for our current (global average) living standards and resource use, isn’t fewer people better?

Collapsing pyramids

Not necessarily. Consider this pyramid:

This is Japan’s demographic pyramid. At least, it should be a pyramid, broad at the base and narrow at the top. As it (precariously) stands now, there are more 50-year-olds than 20-year-olds and more 20-year-olds than 10-year-olds.

Japan is only one example. The pyramids in most Western countries are becoming ‘top heavy’. That is an issue. The healthcare burden - economic and otherwise - will shift (even more) to diseases of old age. There will be fewer people whose productivity can be harvested to pay pensions. Also, a smaller labor force, ever more institutional inertia due to a lower influx of young ambitious people, you name it.

As it is organized now, society is built on the churn of generations, but if the younger generations become less numerous, the weight on their shoulders becomes proportionally heavier. Fewer people have to bankroll the pensions and healthcare costs of the more numerous generations preceding them.

So, on spaceship Earth there are too many people, but in society, there are not enough babies. (Soylent green, anyone?)

Nature and nurture

We’ve been looking at the ‘what’, but what matters most is the ‘why’. That ‘why’ hides in the house of mirrors where nature and nurture meet: culture.

Plenty of people make the conscious choice not to have children. Anti-natalists take this conviction to an extreme end — they think reproduction is morally wrong2, especially in a world that’s struggling with climate change, biodiversity loss, rampant inequality, and so on. But I think they are a minority among those who don’t have (enough) children3, because, in countries with lower birth rates, studies tend to find that most people want more children. The researchers suggest that this disparity between desire and reality is due to:

… contextual factors—norms about parenthood, work–family policies, unemployment—shape women’s fertility goals, total family size, and the gap between them.

Or, culture.

I can’t untangle the many threads that combine into something as complex and changeable as culture, but let me offer a few stray thoughts.

At the country level, declining birth rates coincide with higher levels of education for women, the availability of contraceptives, and adult income levels. With a broad brush, we might say this amounts to female independence and reproductive choice. Those are good things. Honestly, about time! And yet, a lot of women are constrained by the cultural imperative of choosing between two c’s: career or children. Sure, there are many exceptions, but still I’d wager that many women feel the (un?)spoken assumption that they will be the ones who put their careers on hold when the baby arrives4.

It would be too simplistic to point only at our career- and success-driven mindset. Even if we look at the Scandinavian countries, famed for the - by far - best parental leave policies on the planet (close to a full year for both parents, with between 50% and 100% of your regular salary!), we don’t see high birth rates. The larger countries in the Nordic region all have a birth rate below 1.6.

Considering the low birth rates in the most gender-equal, most parental leave-friendly countries in the world, Finnish demographer Anna Rotkirch observes that:

In most societies, having children was a cornerstone of adulthood. Now it’s something you have if you already have everything else. It becomes the capstone.

As this analysis in the British Medical Journal puts it: there are no simplistic solutions. No policy change will change birth rates more than a cultural shift will.

Back- or forward?

However, in those Nordic countries, one thing has briefly turned the birth rates around: the COVID-19 pandemic. 2021 is the only year in (at least) a decade when Nordic birth rates increased. In 2022 they dipped again.

What happened? We can’t be sure, but the women interviewed in the linked National Geographic article said that the lockdowns forced everyone to ‘slow down’ and reconnect with the loved ones in their bubble5. One researcher considers the advent of working from home as a crucial factor, as it could be “a positive way to reconcile work and family domains for women.“

Then why the dip in 20226? The return to the office took place, our agendas filled up again, and building a family7 (for those who want to) drowned in a sea of other culturally desirable boxes to check. To an extent, back to baseline, although in some sectors working from home has - finally and long overdue - become more acceptable.

Most people seem to want (more) kids but they feel too economically precarious (see also the great decoupling), socially unsupported, and culturally discouraged to have them. In the article on Nordic birth rates, Anna Rotkirch, the Finnish demographer we met earlier, wonders:

What would society look like if we valued reproduction, and raising babies, not just your own, as much as [economic] production?

It is telling that the same Henry George who conceived of spaceship Earth was an early proponent of universal basic income, as well as a pension and social support system. In his 1885 speech The Crime of Poverty, he asks the question:

No taxes and a pension for everybody; and why should it not be?

…we might, without degradation to anybody, provide enough to actually secure from want all who were deprived of their natural protectors or met with accident, or any man who should grow so old that he could not work.

Let me finish by putting on my biologist’s hat once more. I don’t think that Earth, as spaceship or set of ecosystems, needs more people. Yet, declining birth rates are straining socioeconomic systems. Instead of pushing people to have more kids with inadequate and sometimes counterproductive policies, can’t we consider that the socioeconomic systems are straining because they are the problem? Case in point: a little over a month, ago, the IRS stated that America’s wealthiest people are evading $150 billion (yes, with a ‘b’) worth of taxes. Each year! What if we use that to provide a universal pension? To fund universal healthcare? Suddenly, the ‘problem’ of low birth rates seems a lot more manageable. Maybe not even a problem at all. Maybe we don’t need to have more kids. Maybe the human population will stabilize at a few billion people less. And maybe, with the right intergenerational support systems, with an emphasis on thriving rather than merely consuming, that need not be a disaster.

In a recent CNN article on plunging fertility rates, Jennifer D. Sciubba, demographer and author of 8 Billion and Counting: How Sex, Death, and Migration Shape Our World, sees three possible scenarios:

Status quo: business as usual. We pointlessly fabricate simple-minded policies to tweak birth rates without results but don’t solve any of the actual issues. (My cynical guess.)

A world of fear: driven by populist fear-mongering, women are coerced into having more children. (My profound worry given recent political actions turning back the clock on reproductive choice.)

Resilience: we adapt our systems to a new age with lower birth rates. (My preference.)

I don’t know what that resilient scenario might look like. But spaceship Earth’s crew quarters need an overhaul.

Do you have or want kids? Or not on the agenda? (All choices are valid; I’m just curious…) Also, this one turned out longer than I intended. Did you like the deeper dive?

A more palatable version might be E.O. Wilson’s Half-Earth proposal of setting aside half of the planet for nature.

Of course, the always bubbly (sarcasm alert) Schopenhauer had his characteristically pessimistic take on having children. In his 1851 Parerga and Paralipomena, he wrote:

If children were brought into the world by an act of pure reason alone, would the human race continue to exist? Would not a man rather have so much sympathy with the coming generation as to spare it the burden of existence?

Consistent with his thoughts, he never had kids.

Of course, you can choose not to have children (or have health issues that prevent you from having them) without being an anti-natalist, which is probably closest to my position, and so, you also know my bias for this essay.

Not to mention that having to host a growing fetus in your womb for nine months isn’t exactly conducive to workaholic tendencies.

Sadly, the lockdowns also coincided with an increase in domestic violence. Be careful about who you invite into your bubble.

Continuing in 2023. Finland, for example, is at 1.28 kids per woman and dropping.

The traditional nuclear family - mom, dad, kids - is only one option, of course, but still (by far) the most prevalent one.

Elon musk is doing more than having 11 children. He is paying autistics, including a woman who did not want children, to play non-secular quiverful. I saw a documentary with one family. The one featured in this story: https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/article/2024/may/25/american-pronatalists-malcolm-and-simone-collins

I thought I wrote about it, but couldn't find it.

I’m 16 and in college getting my associates at the moment. I’m hoping to go on to finish my bachelor’s and go on to graduate school. I love kids and want to raise kids one day, although not my own biological ones because of genetic diseases I deal with. But as you mentioned, I’m unsure how I would navigate a career and children. I want to be present in my children’s life. If the public school system starts to fail them, as it did for me, I want to be able to spend time finding more nurturing education options for them. And at the same time, I need to be able to make a living. One solution I’ve considered is a multi generational household with my parents even as an adult with a career and a partner, so they can be more involved in my children’s life and be able to help when the capitalist system demands my presence. But… yeah I don’t know.