Species Fraud: the Case of the Tibetan Beetle and Audubon's Birds

Also, how DNA barcodes work and why your sushi is (probably) fake

Linnaeus, we have a problem

In 2007, a new beetle species was discovered in Tibet. The beetle, Propomacrus muramotoae, was one of three species in the genus Propomacrus, together with one from the Eastern Mediterranean and one from central China.

Only, the Tibetan beetle is not a new species.

A few weeks ago, scientists applied DNA barcoding to specimens of the Tibetan beetle, and… turns out that it belongs to the Eastern Mediterranean species.

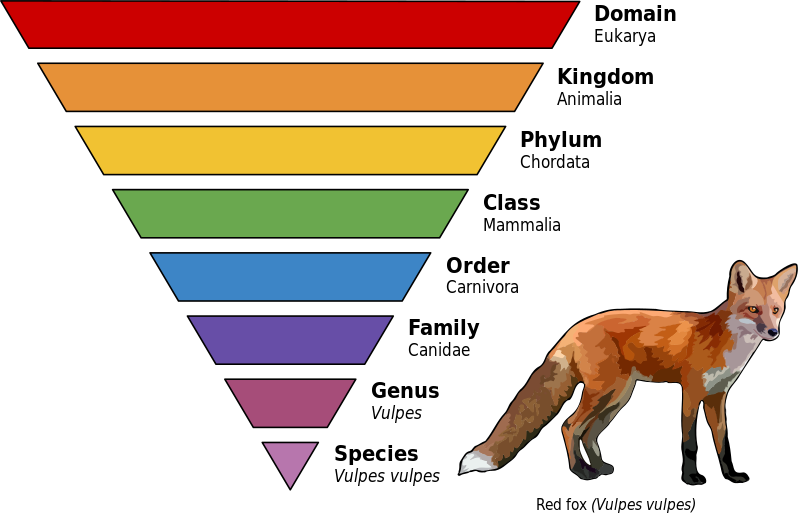

How can a DNA barcode be so certain? After all, despite what we might intuitively think, dividing organisms into species is not always straightforward. While the idea of ‘species’ has been around for quite a while, it was only in the 18th century that Swedish biologist Carl Linnaeus made it his life’s work to inventory and categorize living organisms. To do so, he devised a set of categories that fit into each other like Russian dolls. Species are part of a genus, genera belong to a family, and so on, all the way up to the three domains of life — bacteria, archaea1, and eukaryotes (including yours truly). Not everybody agrees with the three-domain idea, but it’s still the standard view.

Here’s how that works for a red fox.

Neat. Life, however, isn’t always neat. Linnaeus didn’t have any DNA barcodes to go on; he basically looked at organisms and when they looked sufficiently alike: cool, here’s a species. You can see how that could be an issue. Think of insects that undergo metamorphosis. By Linnaeus’ time, scientists knew that caterpillars became butterflies2, but imagine if they hadn’t known. Linnaeus would have surely classified them as entirely different species. Or what about cryptic species that look alike so much that they can easily fool us?

While Linnaeus’ classification system has proven resilient (though that could simply be historical inertia), the way we assign species status has changed — like in relationships, looks aren’t enough. It’s still not a slam dunk, though. A well-known paper in the philosophy of biology counts no less than two dozen species concepts and even today, biologists disagree over which concept makes the most sense. This is known as ‘the species problem’.

The species concept most of us are familiar with is based on Ernst Mayr’s biological species concept: if two organisms of different sexes or mating types can potentially produce fertile offspring, they belong to the same species. Sounds good. Only… hybrids are a thing — ligers (lion and tiger), wholphins (killer whale and dolphin), and pizzly bears3 (polar bear and grizzly), oh my. Those hybrids are usually infertile, but plants, for example, hybridize quite readily. And let’s not even talk about bacteria, which can bud off copies, have massive orgies, and squirt genetic material at will.

Then came DNA sequencing.

DNA barcoding and fake fish

For now, we won’t disturb bacteria orgies, but when it comes to so-called ‘complex’ organisms, surely DNA will give us a good tool to separate one species from another?

To an extent, yes. But remember that the gene pool of a population, always and everywhere, evolves. There are always fuzzy edges and shifting borders within and between species. In the long view, species can split up, be born, or go extinct.

Still, DNA can be helpful. Even so much so that, in animals at least, we have DNA barcodes for (most) species, including the not-really-Tibetan beetle we met earlier. For example, this is the barcode of a human immune cell called a B-lymphocyte:

What are we looking at here? Every colored line represents a nucleotide or ‘DNA letter’: A, C, T, or G. One thing to note is that your immune cell barcode won’t be 100% the same. We all carry our personal mutations, after all. Then how is DNA barcoding useful to delineate species?

To barcode animals, we use a gene with the simple name ‘mitochondrially encoded cytochrome c oxidase I‘. Friends can call it MT-CO1. This gene is quite stable within species, but evolves quickly between species (there are exceptions). This often leads to a barcoding gap — a gap between how much variation we see within species and how much variation we see between species in the MT-CO1 DNA sequence. Thanks to this gap, DNA barcoding can reliably put an organism in the correct species bucket. In the illustration below, if there is a barcoding gap, we can compare two barcodes and if the percentage of variation between them falls in the red distribution, they very, very likely belong to individuals from the same species.

That sounds circular. We use DNA barcoding to identify species, but we need to figure out how much barcode variation there is within and between species to use DNA barcoding… It’s best to see barcoding as a tool for confirmation and classification.

Consider the fish on your plate (if you eat fish, but indulge me). DNA barcoding is popular for catching food fraud and it is a good way to confirm whether or not the fish in your dish is the species it is claimed to be. It often isn’t. Between 26 and 50%(!) of fish in European retail, restaurant, and food service outlets is mislabeled. Or, if you’re in LA and frequent its sushi restaurants, there’s about a 50% chance the fish in your rolls is not what the menu says (with rates up to 77% for halibut, tuna, and snapper).

Let’s return to our beetles.

The mistaken species identity could have been an honest fumble. The (not) Tibetan beetle was described not that long ago, in 2007, but DNA sequencing technology has improved markedly. Besides, identifying insects based on morphology can be notoriously difficult4. However, the authors of the revision claim to have found:

… deliberate modifications in essential diagnostic features during morphological examination… significant fraudulent tampering has occurred with the P. muramotoae specimens.

The Tibetan beetle was (possibly) a forgery.

Which means I need to tell you about a bird.

The bird that wasn’t

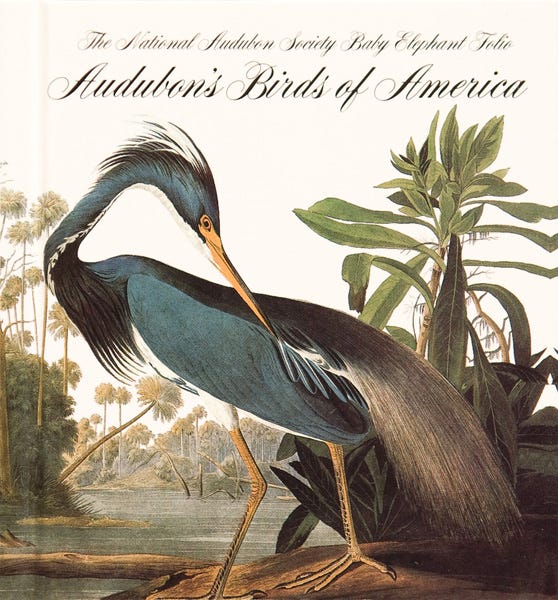

John James Audubon was a French-American naturalist who lived in the late 18th/early 19th century. He combined his passion for art and biology by embarking on the quest to draw all the birds in America. This eventually became a reference work known as - you’ll never guess - The Birds of America.

The book cemented his reputation as a naturalist and, today, a first edition can net you the tidy sum of 6-8 million dollars. One of the oldest environmental organizations in the world (the National Audubon Society) is named after him. During the decade-plus of work John put into the bird book, he described several new species, not in the least the remarkable Bird of Washington (Falco washingtonii) — a regal new species of eagle.

You know what’s coming.

In a forward-thinking influencer move, Audubon invented the new eagle species. A 2020 study dug into the archives and found that Audubon’s ‘Bird of Washington’ was,

… the product of both plagiarism and invention. The preponderance of evidence suggests that the Bird of Washington was an elaborate lie that Audubon concocted to convince members of the English nobility who were sympathetic to American affairs, to subscribe to and promote his work.

Hold up, a new species gets you subscribers? Don’t tell Substack. Also, subscribe, will you? (I had to; I’m sure you understand.)

Audubon milked his favorite bird for quite a while:

Audubon rode his Bird of Washington to widespread fame and then actively maintained the ruse for more than 20 years…

It’s not just this single bird. Audubon pranked other naturalists by making up fish and mammal species and he doctored his own diaries to support make-believe stories of discovering new species. Likewise, the experiments he did with ringing birds as a way to identify and track individuals (now common practice in ornithology) were probably fake. To be fair, he didn’t exclude himself from his lies; he made up stories about his own life and wasn’t shy about using different identities. Documents unearthed in 2021 provide evidence for Audubon’s,

… early identities and pseudonyms, which prove to have been both intentional and strategic…

Despite his lies and scientific misconduct, we might argue that Audubon was ahead of his time in terms of personal branding.

After all, even almost two centuries later, I’m writing about him.

Show me a Substack newsletter that can do that.

I promise I didn’t make anything up in this post. If you enjoyed our tale of species fraud, click hearts, comment, share, etc. The algorithm thanks you.

(If you’re a fellow newsletter writer and think your readers might appreciate my writing, you can recommend Subtle Sparks, if you are so inclined…)

I have a lot more to tell you about these microbial mavericks in a post coming soon — including juicy details about their intimate relationship with Norse gods.

In large part thanks to Maria Sibylla Merian, a 17th-century naturalist who meticulously documented the butterfly metamorphosis and many other facts of insect life.

Yes, that’s one of their actual names. Also known as grolar bears, zebra bears, grizzlars, or nanulaks.

Especially beetles and butterflies, many species of which can only be told apart by the elaborate shape of their - I kid you not - genitalia.

I love this piece! Also I really like your voice as a writer - your pieces always make me chuckle as well as teach me fun new things!

That was a fun read, and the last lines made me laugh!