Pupal Soup

On the past, the future, and the power of goo. Plus recommendations.

Pupal soup

After a caterpillar has eaten several thousand times its own bodyweight, it has finally amassed enough fuel to build a pupa. The hungry little animal spins a thread of silk to fasten itself to a branch, sheds its skin one last time, and seals itself into a hardening chrysalis (the name of a butterfly pupa). Inside, digestive enzymes dissolve much of the caterpillar’s former self during a process known as histolysis. Muscles soften, organs loosen, and the past melts away into what’s called the pupal soup — a sloshy memory of a body, waiting to be rebuilt.

Metamorphosis is both a biological marvel and a mighty metaphor for transformation.

It is tempting to cast ourselves in the role of the caterpillar. Or, perhaps more accurately, the butterfly-in-waiting. That’s what New Year’s resolutions are all about, aren’t they? This year didn’t quite work out as planned, but next year, 2026, will be the year of change, of transformation. The fitness journey, the sabbatical, the new job, the new relationship, the new home, the new you.

We collectively amass extra fuel during our holiday feasts, but, of course, that is only to power our coming transformation.

How does the caterpillar, though, know what to transform into?

Well, the soup is chunky.

Imaginal discs

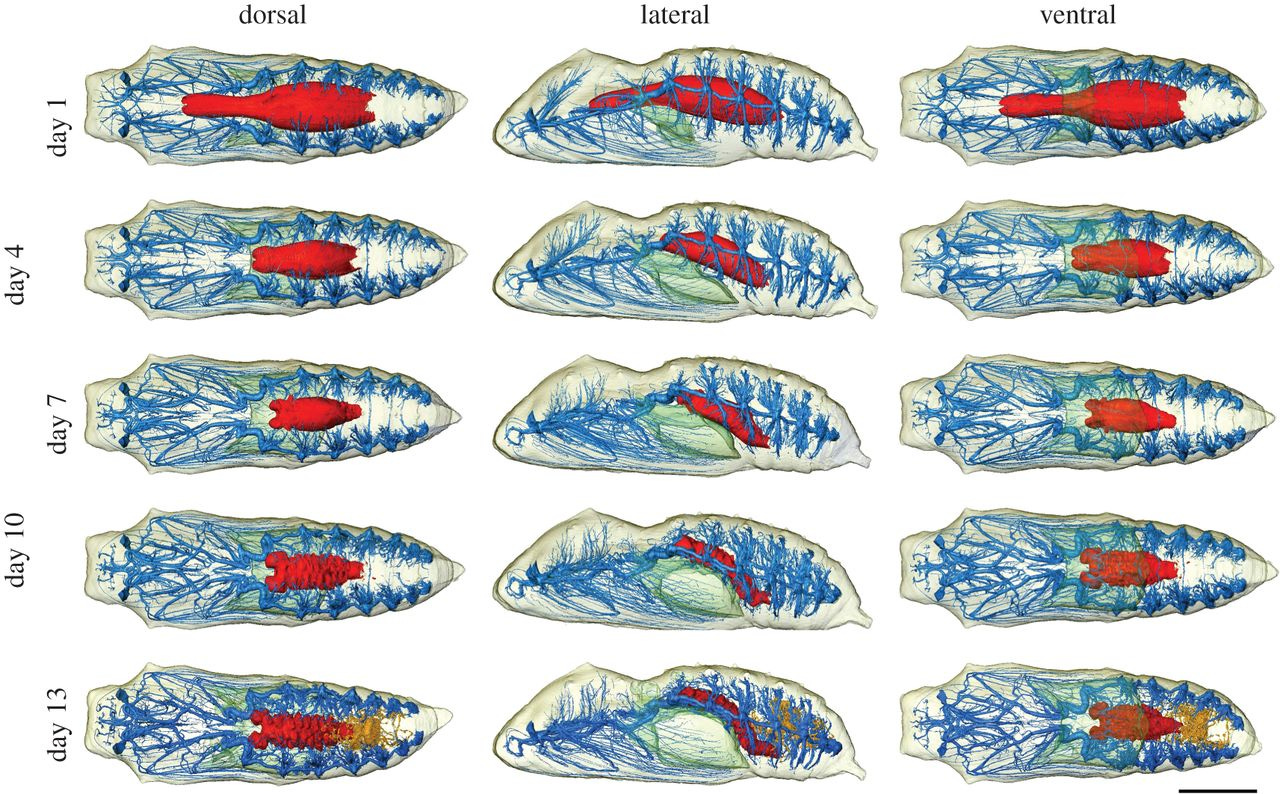

Contrary to popular belief, a caterpillar doesn’t fully liquefy in its chrysalis. While most of its body does turn into a nutrient-rich goo, some tissues remain and reshape, such as parts of the respiratory system and the gut.

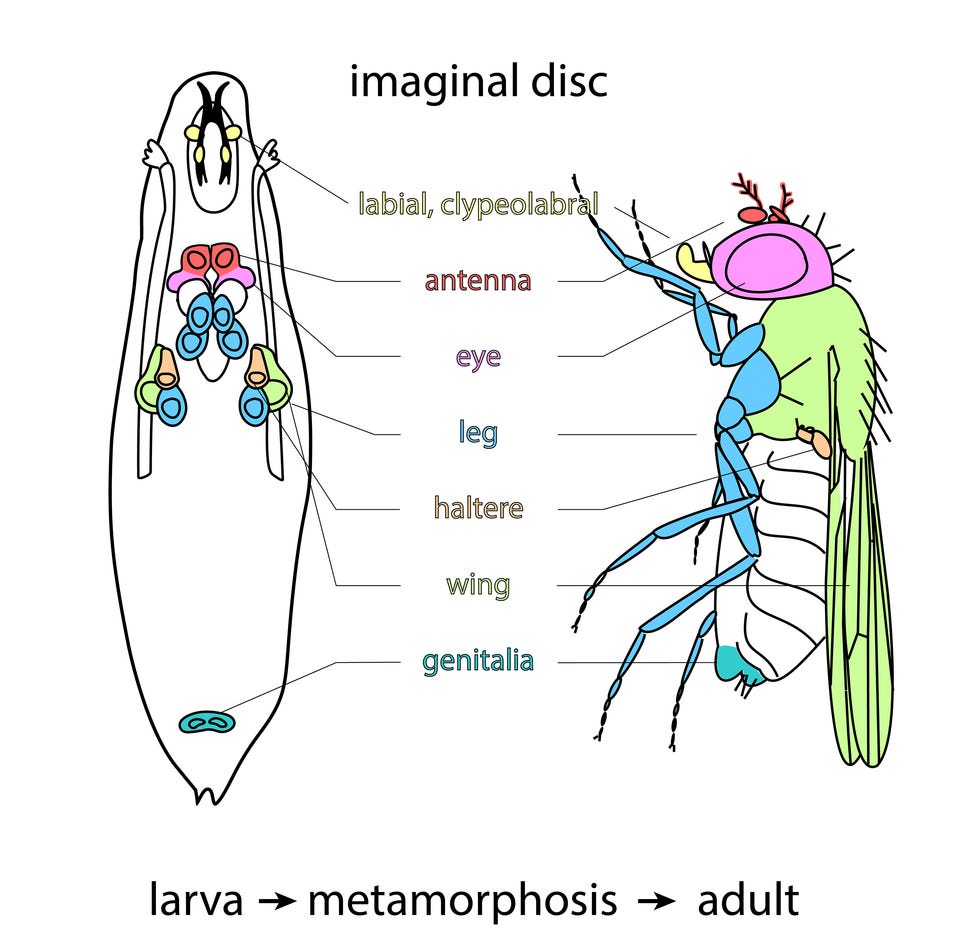

More interesting are clusters of cells called the imaginal discs. Caterpillars develop these discs as an embryo, and they already provide the blueprint for the butterfly they will become. All insects that undergo complete metamorphosis1 have imaginal discs.

Butterflies might even remember (some aspects of) their caterpillar days. This was originally discovered in a study on moths (Manduca sexta, also known as the tobacco hornworm). With the help of little electrical zaps, the scientists conditioned the caterpillars to develop an aversion to a specific odor. That aversion persisted through metamorphosis and into the adult moths. Memories acquired through associative learning probably survive the soup stage because some parts of the brain (like the mushroom bodies, which feels surprisingly apt in soup) don’t get fully gooey-fied.

In our fast-and-loose metaphor, you already carry the blueprint for your transformation.

The trick is finding the discs.

The moth and the flame

Let’s begin with a simple example before we dive into the shifting shadows of my looming identity crisis, an example that feels suitable for the last post of the year: the state of the newsletter.

In the everlasting search for meaning, my writing here has, at some point, been a two-faced god, a monster, and a mycelium. Still, more than anything else, my writing is a trickster.

And now, it itches and aches and groans. Other writers on this platform have noted a decline or plateau in engagement. Feel free to hypothesize about potential causes. Perhaps Substack has become another network for mere celebrity veneration, a Goliath2 teetering toward collapse, a social media platform entering the next stage of enshittification, or an online community that trends toward a growing inequality in which the many want to be the few. Or all of the above, because rarely are things as simple as they seem.

No matter how much I want Subtle Sparks to be a special snowflake, it is no exception. The numbers, for what they are worth, have not been good. Is a metamorphosis in order? For now, I do not know. Let me first attempt to find the newsletter’s discs.

Science, certainly. Nuance, hopefully. Wordplay, inevitably.

What am I missing?

All I can say at the moment is that I will always prioritize ideas over clickbait.

Before I wish you a magnificent new year, we must descend into the cave of the slippery self.

If I ever call myself a butterfly, assume I have been kidnapped and send help. A moth, however, suits me better. Explorer of the night, purveyor of shadows, and yet insatiably and inscrutably drawn to the light3, to the point of burning myself in pursuit of it.

But I am not yet the moth. I am the goo.

My life has changed significantly this year. It will change in the new one as well. What will emerge from the current Christmas-dinner-fueled chrysalis remains unknown. However, I can find imaginal discs, persistent embers of self that have survived previous transformations. A stubborn thoughtfulness, an elemental kindness, an insatiable desire to understand, an enduring capacity for love, a twinkling mischief that only appears when I feel safe… There is raw material to sculpt.

We all have our discs. Yet, with those raw materials in hand, it’s deceptively tempting to slot ourselves into the social templates that we are provided through a combination of culture, upbringing, and past experiences. I can only speak for myself when I write that, while many of these templates partially fit, not one has felt exactly right. Let’s call this the Heraclitan dilemma: by the time you’ve figured out who you want to be, you’ll have changed your mind about it.

Heraclitus seems like just the guy to end this post with. Also known as ‘the dark’ or ‘the obscure’, this ancient Greek philosopher has reached us only through cryptic fragments of a single work. He constructed his worldview based on the core idea that everything is always in flux. Panta rhei (πάντα ῥεῖ), he claimed. Everything flows. You cannot step into the same river twice, because both you and the river have changed.

That forever change, however, has its constraints. You are (for now?) still a human and the river is still a river. Some things persist. Like imaginal discs.

I am goo. I am also the caterpillar and the moth.

And, with a nod to another ancient philosopher, may 2026 bring you all the butterfly transformations you dream of.

See you soon.

Recommendations

To end 2025, here are a few books that you might enjoy if you like this newsletter:

The Light Eaters by Zoë Schlanger (science): A wonderful expedition into plant blindness, intelligence, and - perhaps? - consciousness.

Fluke by Brian Klaas (social science, history): On how small, random chance events can divert our lives and change everything.

Lake of Darkness by Adam Roberts (science fiction): One of the members of a mission sent to study a black hole receives a message from inside the black hole... and kills the other crew members.

There Is No Antimemetics Division by qntm (science fiction): How do you fight a lethal, extinction-level idea that you forget the moment you learn about it?

Katabasis by R.F. Kuang (fantasy): Grad students Alice and Peter travel to and through hell to save their arrogant supervisor in the magical arts.

And here are a few newsletters I inevitably look forward to. They are very much worth your time.

Lessons on Drugs by Lauren Cortis: It’s fun, clever, and will teach you a lot about pharmacology and physiology.

Cognitive Wonderland by Tommy Blanchard: In clear, eminently readable prose, Tommy takes you on a tour through the wonders of neuroscience, philosophy, and the squishy bits in between.

Reminders for Humans by Sarah Quirk: I remain convinced that Sarah is one of the hidden gems of this platform. Scientist’s brain, artist’s soul, writer’s lyricism.

Oscillator by Christina Agapakis: Simply one of the best observers and chroniclers of that wildly intriguing space where biology and technology meet.

Wild Information by Claire L. Evans: A beautiful blend of ecology, computing, and (idea) networks.

Insects like butterflies, moths, and beetles are holometabolous, which means they undergo a complete metamorphosis, including a pupa stage. Other insects, such as dragonflies, aphids, stick insects, and mantises are hemimetabolous, which means they don’t have a pupa stage, but several juvenile forms (nymphs) that already resemble the adult form.

Sidenote: baby mantises are both lethal and adorable. New Year’s resolution unlocked.

My final book of the year is Goliath’s Curse by Luke Kemp, a comprehensive view on the rise and collapse of Goliathan states and empires throughout human history.

Since I just talked about nuance: This is not exactly true. Moths are not attracted to light. Instead, they use the light of the moon as navigation. By orienting themselves with their backs to the moon, moths know which way is up and which way is down. Artificial light, however, screws with this instinct so that they become ‘trapped’ in a spiral around a light source that visually screams louder than the moon.

Lovely post. Very cool about the imaginal discs and the goo. Wishing you all the best in the new year, Gunnar. -S

Can moths fall in love with butterflies? 👀

Asking for a friend.

P.s. you're writing is such a gift. Thank GOODNESS I get to take it into the new year with me.