Olympic Body Dysmorphia

Going for the golden peak

Functional forms

As I start writing this post, the audience cheers on the TV in the background. Not for me, but for the 110m hurdles in the men’s decathlon. I enjoy the Olympics. Where else can you see the world’s top athletes compete in so many disciplines?

And those athletes, holy Olympians, look amazing, especially those in physically demanding sports. What’s interesting to me, though, is that athletes within a discipline look remarkably similar, and athletes among disciplines can look wildly different.

Swimmers are unanimously tall and lanky, broad-shouldered and long-limbed. You can almost hear the audience swoon when they stand there in their swimming suits. Gymnasts, in contrast, have tremendous explosive power in a relatively small package. The throwers (discus, hammer, spear, and shot put) are giants. Marathon runners are slight and light. Sprinters are sleek, lean, and carry a good amount of muscle in their thighs and upper bodies. And so on.

The aphorism ‘form follows function’ comes from early 20th-century American architect Louis Sullivan, but it has found its way to biology as well. If you live in the ocean, a paddle shape is probably a good way to move around. Hence, fins and flippers. Run fast on land? Have long, slim legs with long tendons and most of the muscle in the thigh — a biomechanically advantageous combination of elasticity, reduced drag, and power generation. Think cheetah1 or ostrich for good examples.

If you spend your life training for performance in a specific discipline, you’ll look like, well, an Olympic athlete.

Although… that’s not quite true. Biology is not architecture. No, biology is all about feedback loops wrapped in other feedback loops. In biology, form doesn’t just follow function; function also follows form. Biological form and function feed back into each other because evolution doesn’t optimize; it tinkers. The selection processes that drive evolution require heritable variation in fitness and that requires a ‘form’ to play with2.

Translated to our current topic: how good you are at doing something (function) depends, for a significant part, on the physical gifts you were born with (form).

Your body is the starting point that will affect how good you can potentially do in certain sports. It’s a lot harder (but not impossible) to shoot yourself into the NBA when you’re 5’3’’. Would Simone Biles be the greatest gymnast ever if she would have been 5’10’’ instead of 4’8’’? She could still have been an extraordinary gymnast, but there’s a reason almost all Olympic gymnasts are relatively short and compact. Short means a lower center of gravity, which translates into better jumps, flips, spins, and ‘sticking the landing’3. Compact means better control over that center of gravity because your limbs don’t mess up your angular momentum too much, which translates into better body positioning during flips and spins, and less leverage working against you on many apparatus.

Gymnastics doesn’t stunt your growth, though, no matter which urban myth you may have heard. Assuming adequate nutrition and healthcare, height is largely genetic (with at least 12,000+ gene variants involved!). So why are Olympic gymnasts shorter than average? Because qualifying for the Olympics is a very strict selection process4. People who are naturally shorter and more compact are more likely to become outliers in gymnastic skills and only the outliers among the outliers become Olympians.

Likewise, swimming doesn’t make you taller. But tall, lanky people with broad shoulders have a large surface area, which helps them float, and long limbs with large hands and feet displace a lot of water.

When it comes to Olympic bodies, nature provides the starting point, and nurture (training, nutrition, etc.) sculpts them into their final shape as they ascend Mount Olympus.

Let’s climb another mythical mountain, this one with a slippery peak.

Peak performance

While I enjoy watching the Olympics, it’s also a slightly bittersweet experience. I’m not in bad shape5, but I’ll never be an Olympian, in either form or function. If you want to read the perspective of someone who, unlike me, played sports at the elite level, check out Danielle LeCourt’s wonderful ‘The Olympics are hard for me‘.

The Olympics are both inspiring and intimidating. They make me revel in what humans can do and feel disappointed in what I can(‘t). They make me appreciate the beauty of the human form and lament all the lacks in my own.

Funny thing is, Olympians aren’t Olympian all the time either.

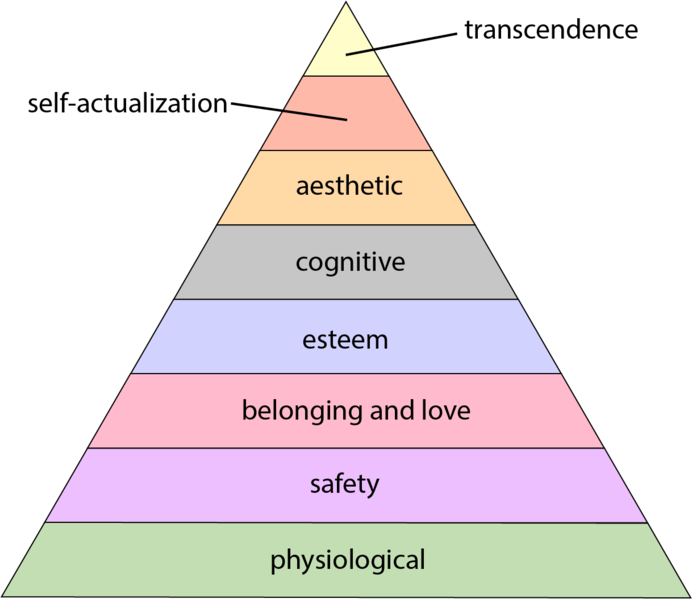

The second mountain for us to climb is actually a pyramid known as Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. I’m sure you’ve seen it. There are several versions, but this one has a shiny golden tip that will illustrate my point:

The idea behind this pyramid is that people climb the pyramid to fulfill their respective needs. Once your physiological needs (water, food…) are met, you'll try to meet your safety needs, and so on, all the way to the glittering tip of the pyramid: transcendence, also known as ‘peak experience’. Maslow himself already recognized that the top of his pyramid is slippery. The human (mind+body) is not made for extended periods of peak experience. You’d burn through your synapses in no time.

This has a parallel in Olympic sports — athletes often talk about peaking. In the months and weeks before the Olympics, they take their training to the next level. Everything - workouts, nutrition, recovery - is dialed in and locked down even more than usual. It’s a complex calculation to ensure that their minds and bodies ‘peak’ at the right time for a once-in-a-season performance. But, like Maslow’s pyramid’s slippery top, this peak performance isn’t sustainable, which is why a lot of athletes ‘deload’ after the Olympics. They reduce their training volume and loosen the dietary belt for at least a few weeks.

That deload rarely gets televised, which is how body dysmorphia (“a mental disorder defined by an overwhelming preoccupation with a perceived flaw in one's physical appearance“) is born. If we compare ourselves to peak Olympians, we forget that most Olympians only spent a limited time on that peak6. We don’t see the hurt, the sacrifice, the failure. The endless weeks of training, the painful injuries, the strain on friend- and relationships.

Here’s another example: bodybuilding. Bodybuilders peak when they participate in a show. They pump themselves with enough drugs to kill a few dozen elephants7 so that they can hold on to muscle while meticulously dehydrating themselves and dieting to barely survivable levels of body fat. The social media pictures look awesome, though. Actually, we don’t have to go to the spray-tanned muscle mass monsters; regular fitfluencers will do. Even if we set aside the ubiquitous filters and the ambiguous blessings of Photoshop, young (wo)men see others become strong and muscular, or perfectly curved, beyond their wildest dreams. Of course, these young (wo)men will feel inadequate8. Never mind that many of their social media exemplars, male and female, may shave years off their lives by taking (entirely unnecessary) testosterone and other performance-enhancing drugs.

All bodies are beautiful and capable, we hear.

Except our own, of course9.

Time for a workout — not to be an Olympian, not to look a certain way, but to nurture my nature.

I’m curious. What’s your favorite Olympic event? Who’s the most inspirational athlete?

Also, if you want to select my newsletter for the Substack Olympics, click hearts, share it, etc. Perhaps even sponsor these verbal gymnastics by considering a paid subscription…

(If you’re a fellow newsletter writer and think your readers might appreciate my writing, you can recommend Subtle Sparks, if you are so inclined…)

Your fun biology fact of the week: cheetahs also have a uniquely flexible spine that helps them achieve a remarkable top-speed quickly.

This is not the full story. Far from it. Internal, physiological processes are subject to selection too.

Women, on average, have a lower center of gravity than men, which is why female gymnasts absolutely dominate men with their floor routines.

Not to be confused with selection in the evolutionary sense. Unless Olympians go on to have more kids than average.

My imposter syndrome is standing behind me with a baseball bat, so this is the most positive thing I’m allowed to say about myself. (Send help.)

This is why the period after a big competition can be challenging. Not only is the athlete’s body sore all over, but they will also see and feel themselves descend from their peak, which is mentally very tough.

This is not entirely fair; there are tested federations and competitions in which only ‘natural’ bodybuilders can compete.

More specifically, this review finds that passive and appearance-based social media use is strongly related to body image dissatisfaction and body dysmorphic disorder symptoms. Yes, in both women and men when you equate time spent on social media (young women are more likely to spend more time on social media than young men).

No, just me? Okay, cool.

I was excited to see this one come through! As a gymnast-turned-volleyballer (true story), I know this lesson all too well (and thanks for the shoutout!). I’ve also seen and heard (and experienced) my fair share of dysmorphia, and while they did used to teach us about this at a once-a-year talk with the university dietitian (and it was introduced to us as part of the female athlete triad, a medical condition female athletes can run into that includes eating disorders, amenorrhea, and osteoporosis), there wasn’t a ton of emphasis on actually helping us remain healthy in that way because the system definitely incentivizes physical optimization over long-term physical and mental health. That said, I think athletes at these top levels have really helped to shift the conversation more towards long-term health in recent years.

But also, I heard once and didn’t follow up to look into whether it was true (I just chose to believe it because confirmation bias!) that bodies that experienced consistent strength training during the earlier years of life tend to retain that ability for muscle mass throughout the entirety of their life (like, it’s forever easier to get back into shape once they fall out of it). Do you know anything about this? I wonder what the mechanism would be if that was true.

Great post!

Re: footnotes 5 and 9: Hey, Gunnar's self-esteem! Leave him alone! He's doing a good job!

Also, re: those footnotes and athletics being inspiring and intimidating: I don't get to watch much of the Olympics except for clips on YouTube because of internet and copyright restrictions where I live (and, honestly, not caring enough to find a pirate source to watch.) I do get to watch and participate in athletic events on our tiny island. And what's really striking to me is how amazing humans in general are in using their bodies, and how little difference there is between elite athletes and people who are just in ok shape.

So, for instance, the world's record for men's squat is 1052 pounds. But the champion for men's squat on our tiny island of fewer than 2000 people is ~500 pounds, which, sure, is less than half of the world record but not that far off. There's a 6 K, 3 K of elevation gain trail run here every year. The world record holder for that kind of event can complete it in about 45 minutes. Our fastest runner completes it in about 48 minutes. And I, a 5'2", overweight, 50 year old woman who never even went to the gym until about 10 years ago can complete it in just under 2 hours. Which is actually pretty close, when you think about it.

Of course watching Simone Biles do flips like she's an anime character is stunning, and of course normal folks won't ever be able to achieve those heights. But the fact that normal people can still do flips at all is pretty amazing. I think that people would be happier if they didn't compare their abilities to those of elite athletes in terms of what the normal people can't do, but in terms of what we can. Because all humans have a lot of really remarkable capabilities that we shouldn't let go unrecognized just because they're not as super-remarkable as someone on TV.