Tsundoku

Good data is hard to find, but this article from publisher Penguin states that the average American reader reads around 12 books per year. However, that number is skewed to the high side due to some unstoppable bookworms. Four was the most reported number of books read annually. In the UK, it’s fairly similar. Only a third of readers say they read more than 10 books per year.

Overall, if you read more than 10 books per year, you might classify yourself as a heavy reader.

Hello, my name is Gunnar and I am a heavy reader.

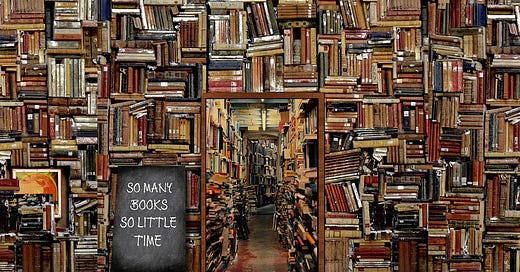

I try to read at least one book per week (on a yearly basis, this probably ends up being roughly 60% fiction, 35% non-fiction, and 5% poetry). During the lockdown year, I got close to two/week. And yet, I get nervous when I don’t have a little stack of unread books waiting for me. It’s my tsundoku heap. Around five years ago, the term tsundoku found its way into global popular media, even though it probably arose in late 19th century Japanese slang, combining the characters for ‘pile' up’ and ‘reading books’.

It me.

As a result, my ascent onto the ‘books to read’ mountain never gets much shorter. Sisyphus rolled a rock up a hill over and over; I do the same with piles of books. (I kid you not, but as I am writing this, the doorbell rings. A book delivery*.)

It’s a beautiful struggle. I would encourage you to try it. Growing up around books (thanks, dad) enhances adult literacy, numeracy, and technology skills in societies across the globe. As an adult, reading - especially fiction - helps you hone your social skills and it improves your empathy. Reading fiction also boosts your cognitive skills and might help you manage your mood. Heck, reading all kinds of books might even make you live longer. (Warning: correlation is not causation. Sounds great, though.)

The world can use more empathy. Grab a book.

(*The Mountain in the Sea by Ray Nadler and Notes of a Native Son by James Baldwin in case you’re wondering. Three cheers for holiday gift cards.)

Antilibrary

Bookish benefits extend beyond the powers of reading, though. Being a voracious reader leads to collecting an anti-library: books you have acquired but not read yet.

In its current form, the concept of an antilibrary was articulated by Nassim Nicholas Taleb in his book Black Swan. He writes:

…library should contain as much of what you do not know as your financial means, mortgage rates, and the currently tight real-estate market allows you to put there. You will accumulate more knowledge and more books as you grow older, and the growing number of unread books on the shelves will look at you menacingly. Indeed, the more you know, the larger the rows of unread books. Let us call this collection of unread books an antilibrary.

The number one reason to build an antilibrary, according to Taleb, is intellectual humility. A good, diverse antilibrary reminds you of all the things you do not know yet and all the stories and wonderful worlds that are waiting to be explored.

An antilibrary is a vaccination against the Dunning-Krüger effect, the widely observed bias most of us have to consistently overestimate our abilities and knowledge. This effect tends to get stronger the less someone knows. People with little knowledge tend to see themselves as being exceptionally knowledgeable. *social media entered the chat*

Very few people are immune to the Dunning-Krüger effect. There may be an exception for people who struggle/have struggled with depression. The depressive realism hypothesis proposes that they might actually see reality more accurately than people without (a history of) depression. (This is not without its critics. People with depression also show certain biases in self-assessments, both positive and negative.)

Try to avoid depression, though. Trust me, it truly sucks.

Just build an antilibrary.

Tsundoku 2.0

Everything, however, has a dark side. (I’m always fun to hang out with, why do you ask?)

Our reading habits have changed in the last decade. While true bibliophiles still amass physical books to build their private (anti)libraries, reading has become a multimedia experience. There are e-books, audiobooks (does that count as reading?), blogs, newsletters, and apps/sites that summarize books for you.

Our antilibrary has grown entire new sections. The problem with some parts of those new sections is that they’re more aggressive with their claims on our attention. We get pings, reminders, and e-mails to make sure that often bland and uninspired content is rammed down our throats.

The beauty of an antilibrary is that it engenders intellectual humility and aimless wandering through ideas until, serendipitously, you encounter something new, something original, something unique. The engagement-driven nature of a lot (most?) online content makes this harder (but not impossible); it’s all similar content with the sole aim of going viral. This multimedia tsundoku can leave us overwhelmed by content that is pushed on us through algorithms that focus on engagement rather than quality.

The solution? Curation. Put some thought into building your (anti)library. How do you do that without having read the books? Look at the source. Is it trustworthy? Does it emphasize quality over quantity? Do you already know the author?

But of course, you should absolutely give new authors a try! Then, consider the recommender. Is it a person/website/reviewer you trust? Have you read an insightful interview with the author? And so on. (Please support debut and established authors alike, the publishing industry is a cutthroat business and most full-time authors struggle to make ends meet. Don’t be fooled by the few unicorns.)

Over to you. If you had to recommend one book - and one book only - to convert someone from a non-reader to a library builder, what would it be?

Youth : "Sophie's World" by Jostein Gaarder

Non-fiction : "The Greek World" by W.Durant (old history book with historical mistakes but still the best overview ever)

Fiction : "The House of Leaves" by Mark Danielewski (for geeks!)

I know, these are 3 books instead of 1, but who's counting..

(thanks, son)