What is expertise? Let me opt for the lazy solution here and check the Cambridge dictionary:

“a high level of knowledge or skill”

Okay, well, that’s pretty… vague, isn’t it? Define ‘high’. And ‘level’. And what exactly is ‘knowledge’ or ‘skill’?

Stop, rabbit hole coming up.

Even a vague definition can give us some clues.

Reaching a ‘high level’ in anything requires time and effort. Acquiring ‘knowledge’ and ‘skill’ implies (self-)education and/or experience. So, gaining expertise is the result of putting in time and effort to gather, interpret, and understand the current state of knowledge in a certain field of inquiry, or to develop a specific skill set. By no means a perfect definition, but it seems to encapsulate the common sense notion of expertise.

Does this mean you need to have a medal, prize, or Ph.D. to be an expert? No, none of these is necessary. Is any of these sufficient? Doubtful.

Then what makes an expert?

Possessing knowledge/skills? Or having those plus the dedication to maintain them and constantly update them as new data comes in? Or all of the above plus the wisdom to recognize and acknowledge the limits of one’s expertise?

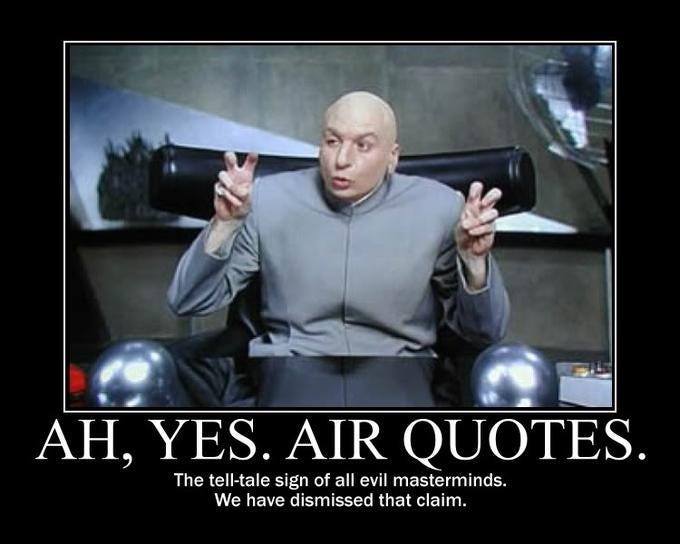

Experts, it seems, can come in many shapes and sizes. Experts and ‘experts’ are not necessarily the same. Quotation marks matter.

Granted, the difference is not always easy to spot.

Good — but not entirely foolproof — tip: people who call themselves experts tend to be ‘experts’.

If everyone can claim to be an expert, how do we know which experts to trust?

Credentials? Sure, those can help. But even the most credentialed person can be biased (if you’ve read some of my other posts, you’ll know that I think everyone is biased in some way). And even the most acclaimed level of expertise can be used for less-than-noble goals.

This adds another level — and explains the title of this post. Expertise is valuable, but experts can be disingenuous or — hopefully rarely — downright malevolent. Note the word ‘can’. In no way do I imply that experts are ‘bad’ or ‘untrustworthy’.

But a few bad apples can do a lot of damage.

Anyway, trustworthy experts need to have more than expertise. They should disclose the extent (and thus limits) of their expertise, and do their utmost to use their knowledge/skills beneficially.

As this book chapter by three psychologists argues, trust in expertise requires more than the recognition of the knowledge/skills encompassed by that expertise. It also requires:

“… vigilance towards the risk of being misinformed.”

Interestingly, the authors argue that trust (they are specifically talking about epistemic trust, but let us assume that this corresponds roughly to trust as we’ve been discussing it here) has three critical characteristics:

expertise

integrity, and

benevolence.

This nicely mirrors what I wrote in the previous paragraph. I did not plan this, I promise. A trustworthy expert, then, is someone who knows stuff (expertise), is honest about the limits of their knowledge (integrity), and is dedicated to using that knowledge to help others (benevolence).

But hey, I’m no expert.

Related thoughts:

Thanks for reading; I genuinely appreciate it. Share the thing, yeah?