Fear (Or, Little Albert and the Burden of Ajax)

In which we learn from little kids and ancient soldiers

I came across a Maya Angelou quote recently:

What is a fear of living? It's being preeminently afraid of dying. It is not doing what you came here to do, out of timidity and spinelessness. The antidote is to take full responsibility for yourself - for the time you take up and the space you occupy.

It’s like she knows me. I’ve always felt like I take up too much space and at the same time like I’m invisible. Like I am too much or too little, but never just enough. Above all, I am afraid.

I don’t know when it started. It’s hard to remember but I was a happy kid, class clown even. That kid is still in me, but he has become afraid to come out and play.

To understand the fear of that inner kid, I have to meet another kid first.

Meet little Albert.

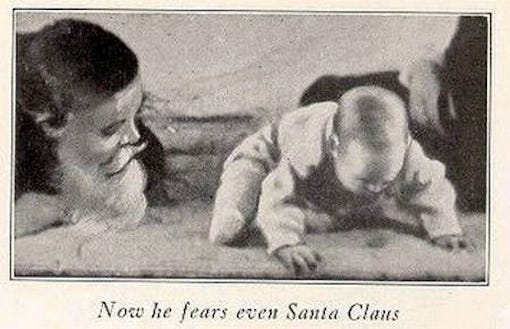

Albert (not his real name) was a 3-year-old boy who was chosen to participate in a wildly unethical experiment, which was published in 1920. Psychologists John Watson and Rosalie Rayner wanted to see if they could condition phobia (technically, an extreme and irrational fear of something) into a child. Albert was allowed to play with a white rat. All good. Then, every time Albert engaged with the rat, our two psychologists started banging a steel bar with a hammer, startling and scaring Albert.

After a while, the sight of a rat terrified little Albert — metal banging no longer required. Follow-up experiments suggested that he had become afraid of furry rabbits, small dogs, and even Santa Claus masks as well. (The lack of detailed records has led other psychologists to question the findings.)

The point: fear can be conditioned.

Let’s take that fear and poke it.

The biology of fear is a remarkably complicated topic. Fear is a universal human experience (Franz Kafka, being Kafka, took it further when he said: “My 'fear' is my substance, and probably the best part of me.”). Intuitively, most of us are convinced that the ability to feel fear extends to many other animals.

That’s where the problem starts: fear has two faces —the biological one and the feeling one.

There are the biological, subconscious processes that we link to fear; shallow breathing, clammy hands, racing heart, and so on. But fear also has a subjective side, and that’s what most of us think about when we think about our fear - the emotional, visceral feeling that comes with it. This makes fear hard to study, especially when we try to translate findings in lab animal physiology to human subjective experience. There are physiological mechanisms that kick into gear when we perceive a threat, and then there is conscious fear. They are related and tied into feedback loops, but not the same.

As little Albert taught us, we can elicit the spine-curling subjective experience of fear without facing something that is objectively a threat. This is what happens when trauma is triggered, a term that has a specific meaning, which ancient Greek tragedian Sophocles* understood better than some of today’s ‘influencers’. Sophocles knew that:

To him who is in fear everything rustles.

Fear is sensible when it alerts you to a threat, but it becomes unbearable when all you see is threats. The only recourse your body has at that point is to become perpetually afraid, avoid everything, or become numb. Those are the three major trauma responses: fight, flight, or freeze. That’s why most forms of therapy for anxiety and related conditions try to decouple the trigger from the response. Identify the trigger, assess objectively whether it warrants the extent of the response, and cut the ties between any unthreatening trigger and the fear response. Different forms of therapy do this in different ways (medication, talking, breathwork, even yoga — the body keeps the score, after all), but the idea is essentially the same: decondition yourself and reclaim ownership of your fear. (Litany of fear, anyone?)

So let me try to own my fear.

It’s a tricky bastard, though. There is no trauma in my privileged past and the only trigger I can identify so far is the feeling of being made out of crappy marble. Because the thing that elicits my fear is shapeless, I don’t know the proper response, which is why I try to fight, flee, and freeze at the same time. Not my brightest idea.

Perhaps it is a fear of failure; a fear of rejection. A fear of never being enough, of being too small or too big. Perhaps that fear is the little kid trying to get out.

Perhaps I should let him.

Avoiding danger is no safer in the long run than outright exposure. The fearful are caught as often as the bold.

— Helen Keller

* Sophocles - having lived through both Persian wars and the Peloponnesian one - was intimately familiar with the devastating effects of war on the human psyche. For example, the image header above this post is the Greek hero Ajax preparing to take his own life. Sophocles’ play Ajax is considered one of the earliest (and still most accurate!) depictions of PTSD. Even today, the play is used to help veterans from the Vietnam War and the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts address their traumas.

Related thoughts:

Um, I was trying to say: hang in there, mate; she’ll be right - to use old Australian slang (as I am an old Australian). I admire your work and hope to help you do write more.

Fear is an emotion and IMHO emotions are triggered by anticipation. Most fears are resolved by experiencing the difference between anticipation and experience. In the case of the fear of death you can’t have the experience, so the antidote, may be to change the expectation. Expecting a pleasant life after death is a start.